CONNECTED | Dec 19, 2025

Artist Edmonia Lewis visited Boston women sculptors in Rome in December, 1865

It was late December 1865, and the United States was still smoldering after five years of civil war. That winter, sculptor Edmonia Lewis stepped onto the streets of Rome and into a new world of possibilities. Thanks to the support of Black and white abolitionists from Boston who funded her travels to Europe, and to the warm welcome of an international community of artists, she began a storied life in the Eternal City. Within only a few years of her arrival in Italy, Edmonia Lewis would become the first Black and Indigenous woman artist to achieve widespread international acclaim.

Opening at PEM in February 2026, Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone is the first comprehensive survey of the sculptor’s remarkable art and life.

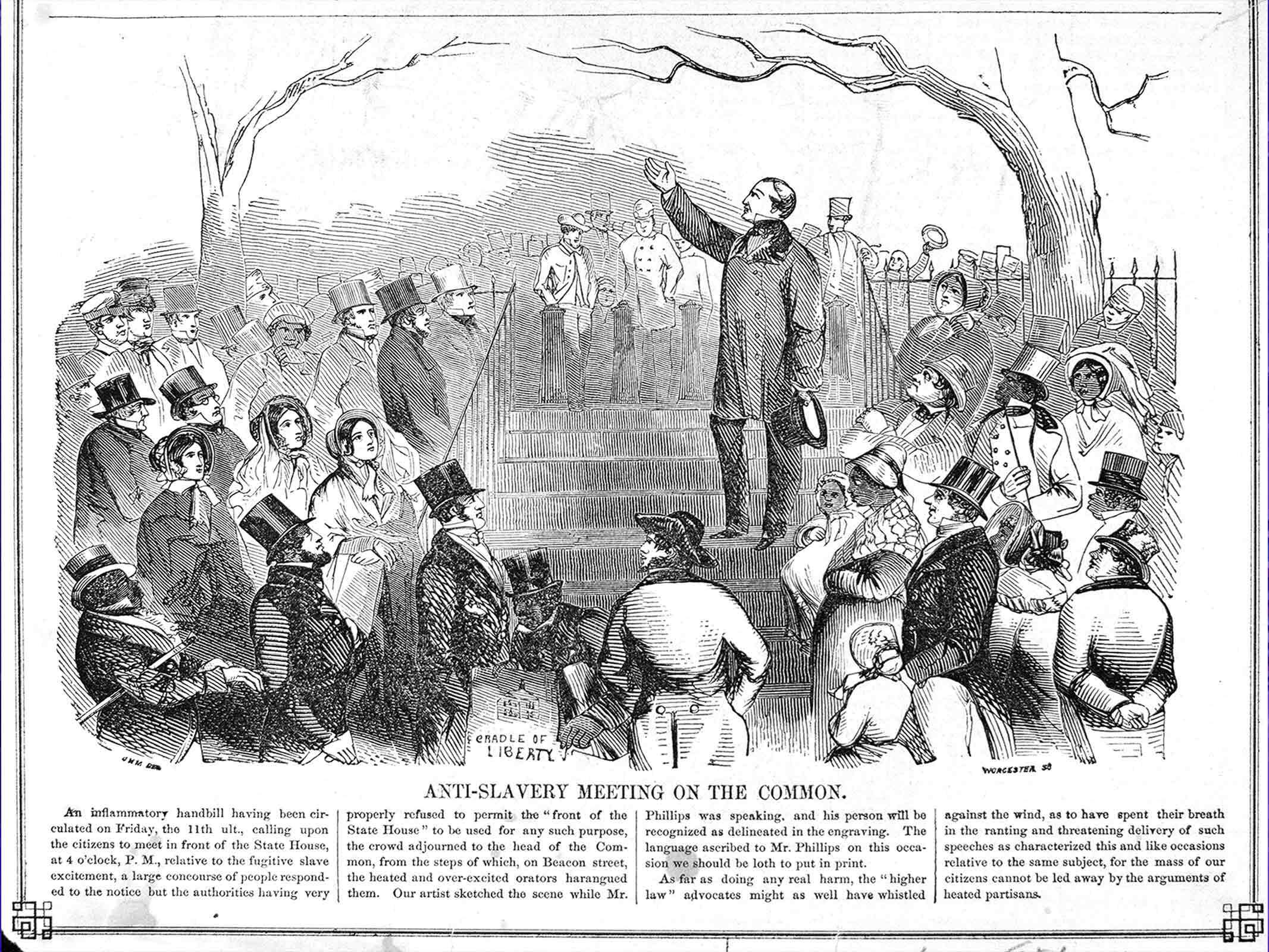

Lewis’ ties to Boston are well known: She arrived in the city in 1863, following the advice of abolitionist Frederick Douglass to “seek the East,” and began her pursuit of an artistic career. A hotbed of antislavery activism, Boston was a place where Lewis could stake her claim as an artist of color with a powerful point of view.

“Anti-Slavery Meeting on the [Boston] Common,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, May 1851. From The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

But several discoveries made during research for PEM’s Edmonia Lewis exhibition have made its 2026 debut in Salem even more fortuitous. When Lewis arrived in Rome from Florence in late 1865, she brought with her a letter to Mary Elizabeth Williams and Abigail Osgood Williams, two sisters from Salem who had been living and painting in Italy as part of an expatriate community of American artists. (The Williams sisters lived in Rome from 1860 until 1878, when they returned to Salem and opened a gallery and school for aspiring young women artists, such as Salem-born painter Fidelia Bridges.)

As the sculptor Florence Freeman recalled in a letter to her family on December 25, 1865, the Williams sisters “went out with [Lewis] at once and before the end of the day had established her in a cozy little apartment, and engaged a studio.” The Williams sisters likely helped Lewis secure a studio at Vicolo della Frezza, no. 57, a former studio building of the great neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova. Several years earlier, another Salem artist, the sculptor Louisa Lander, had worked on the first floor of that building.

Sommer and Behles, Scala della Piazza di Spagna (Roma), 1865–1870. Albumen silver print. Courtesy of the Getty Museum.

The space was just off the Piazza di Spagna, in a neighborhood where many American artists, including leading woman sculptors like Harriet Hosmer, had their studios, and where patrons such as the American actor Charlotte Cushman often circulated in their efforts to promote expatriate artists back home. Among other commitments of support to Lewis, Cushman organized a fundraiser to donate a copy of Lewis’ Old Arrow Maker to the YMCA of Boston in 1867.

No longer a stranger in a new city, Lewis would sit down with the Williams sisters, Freeman and several others for Christmas dinner in December 1865 as a new member of this sisterhood of American artists. Through their friendship, her sculpture became another living link between Salem, Greater Boston and the international art world.

Mary Elizabeth Williams, Falls of Tivoli, Italy, about 1860-75. Oil on canvas. Gift of the Estate of Mary Elizabeth Williams and Abigail Osgood Williams, 1919, 108321.

A painting in PEM’s collection by Mary Elizabeth Williams further conveys the Williams’ and Lewis’ shared connections to the American expatriate community in Italy. In The Falls of Tivoli, Italy, Mary Williams shows the famous waterfalls that tumble over terraced hillsides into the Aniene River as it threads through the landscape northeast of Rome. The town itself, perched dramatically over cliffs, is visible in the middleground. Lewis spent time in Tivoli on multiple occasions. As Freeman recounted in other letters, Lewis often traveled there with fellow Roman Catholic expatriates like Isobel Curtis Cholmeley, who would serve as Lewis’ godmother at her baptism, and Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, a close friend of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, who was himself a Catholic convert. These excursions to Tivoli, likely filled with rich conversation and beautiful music, mirrored the much more modest gatherings that Lewis hosted in her own apartment in Rome — gatherings that the Williams sisters, Freeman and others attended where, after serving her guests a meal, Lewis often took out a guitar and sang for her friends.

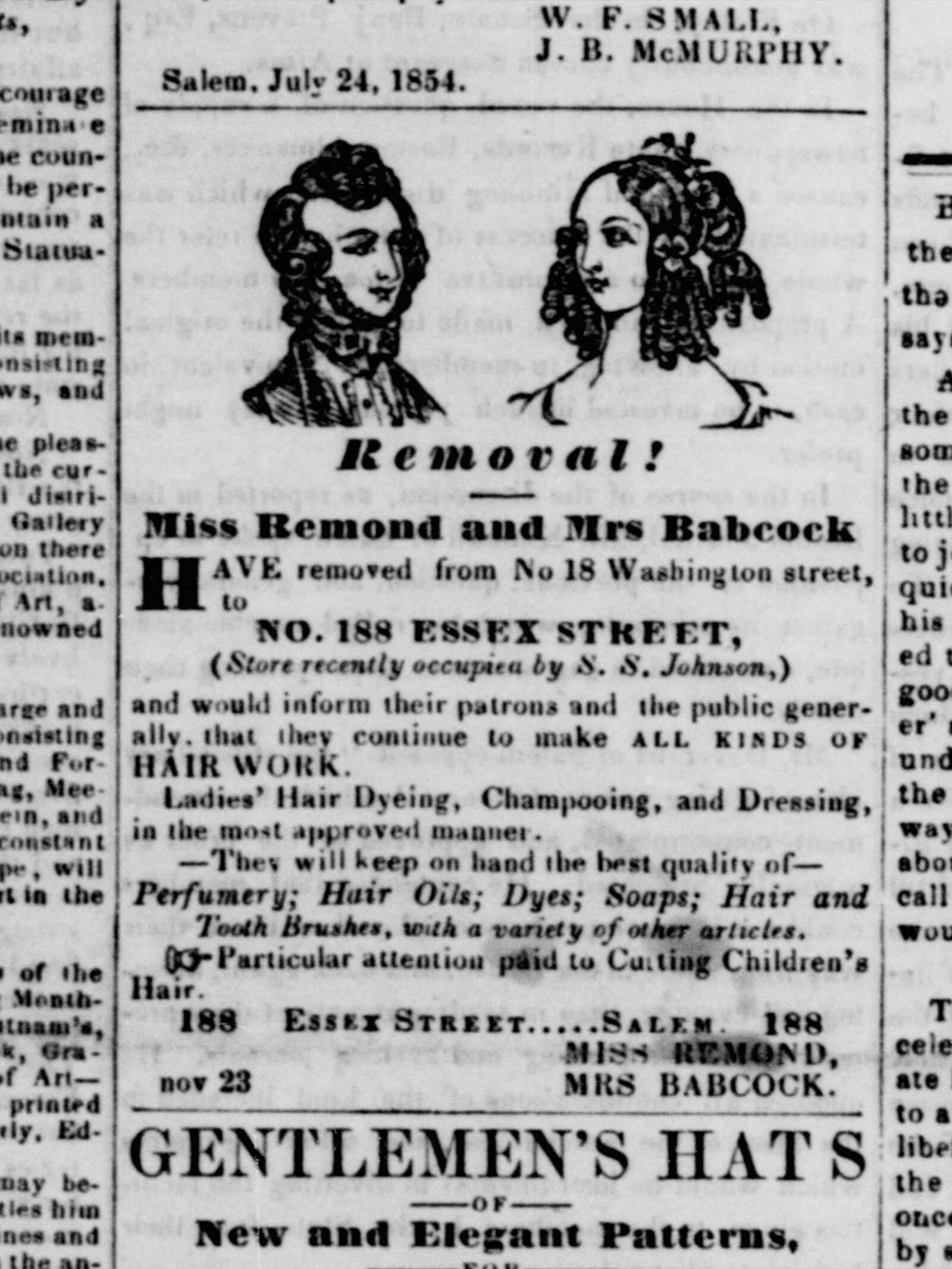

But the Williams sisters were not Lewis’ first friends from Salem. Lewis’ connections also extended to an international community of Black activists and intellectuals centered around Boston in the 1860s, which included the Remond and Babcock families of Salem. Lewis made her exhibition debut as an artist in October 1864 at a fair organized by the Colored Ladies’ Sanitary Commission of Boston, led at that time by Christiana Carteaux Bannister. Before marrying the painter Edward Mitchell Bannister, Christiana worked in the Remond family’s Essex Street salon, and her brother Charles Babcock would marry Cecelia Remond. Bannister, the Remonds and Lewis were part of a circle of Black women during the Civil War era who used art to forge new forms of solidarity and selfhood.

Lewis perhaps also found connection with individuals like Christiana Bannister and the Remond family because of their work as hairdressers. (Her brother Samuel, who lent her financial support throughout his lifetime, made his fortune in large part through his work as a barber.) Hairdressing was not only a practice of skill and invention, but also a means of expressing autonomy and conveying care in slavery’s aftermath. Salons like Bannister’s shop in Boston and the Remond family business at 188 Essex Street in Salem offered a space of service and self-making, where Black customers could craft their appearance apart from and in spite of white beauty standards.

After her move abroad, Lewis would also befriend Sarah Parker Remond and Caroline Remond Putnam — fellow expatriates living in Italy, and mutual friends of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who visited them all on his European honeymoon in 1887. Once again, Lewis’ story reveals Salem as a place where the local and global intersect. For Lewis, several friendships at some of the most pivotal moments in her career trace their way back to this small town on Boston’s North Shore.

Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone opens on February 14. Join us on opening day for “Whose Memory Do You Carry?”, an artist and curator talk about Lewis’ legacy.

The exhibition is co-organized by the Peabody Essex Museum and the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia. Major support is provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art, the Henry Luce Foundation, the Wyeth Foundation for American Art, Carolyn and Peter S. Lynch and The Lynch Foundation, and Karla and Jeff Kaneb. We thank Jennifer and Andrew Borggaard, James B. and Mary Lou Hawkes, The Creighton Family, Chip and Susan Robie, Karla and Jeff Kaneb, Timothy T. Hilton, and an anonymous donor as supporters of the Exhibition Innovation Fund. We also recognize the generosity of the East India Marine Associates of the Peabody Essex Museum.

BLOG

Familiar faces: A painted detail echoes a figurehead from PEM’s collection

6 Min read

Press Release

PEM debuts the first major retrospective exhibition of acclaimed 19th-century Black, Indigenous sculptor

BLOG

Curator Q&A: Behind the Scenes of Making History: 200 Years of American Art

8 min read

Exhibition

Let None Be Excluded: The Origins of Equal School Rights in Salem

April 23, 2022 to April 28, 2024