Thousands of American citizens have been torn from their country and from everything dear to them: they have been dragged on board ships of war of a foreign nation.

—Madison, 1 June 1812

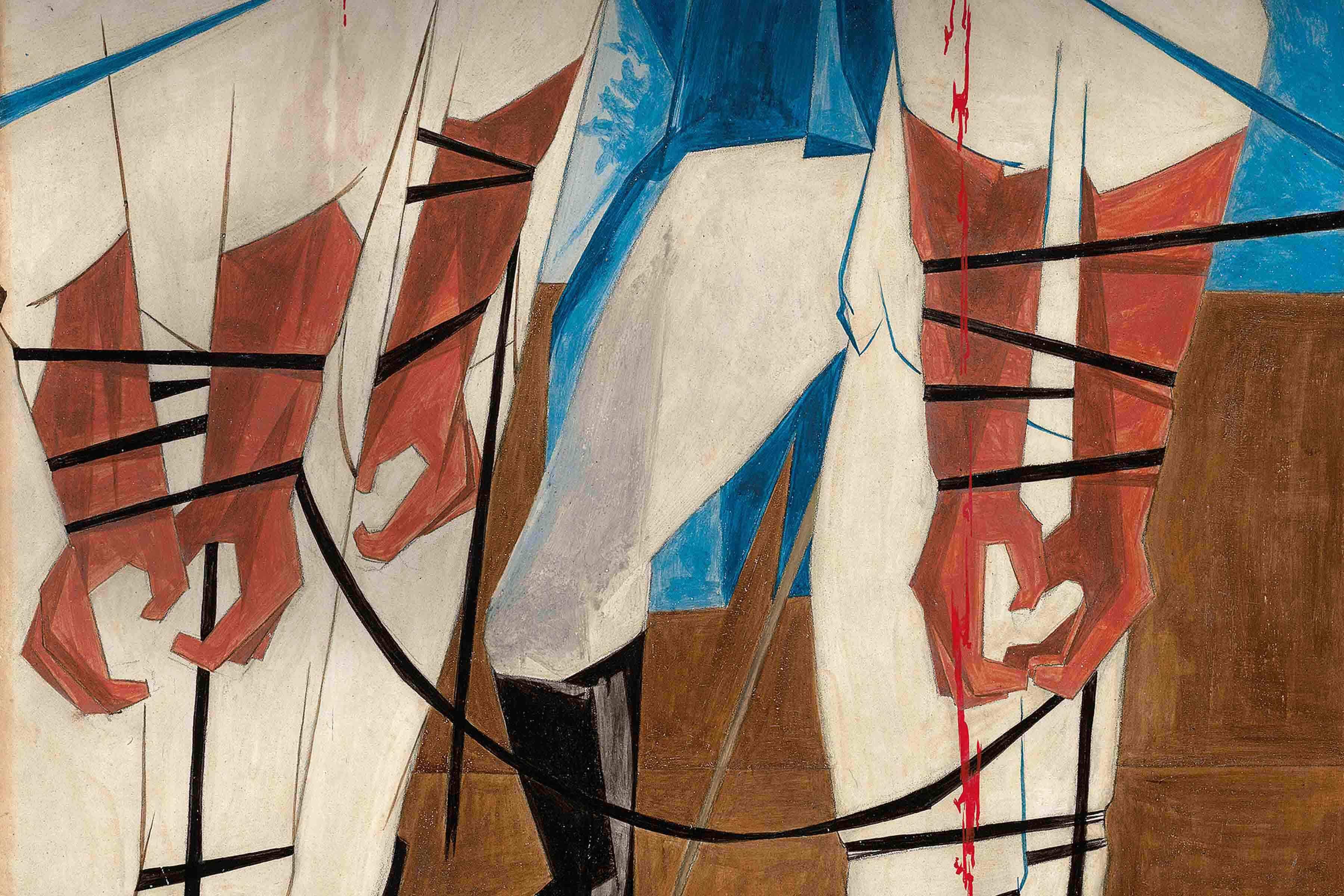

During the years leading up to the War of 1812, the British Royal Navy arrested American sailors in international waters and forced them into their service in a practice known as impressment. These activities were a justifiable pretext for war as articulated in President James Madison’s request to Congress, which Lawrence excerpted for this panel’s title caption. In this painting, Lawrence depicted nameless, faceless American sailors who have been captured and bound. To evoke similarities between the act of enslavement and forcible impressment, Lawrence pictured the men held at bloody sword point and made to march in a stacked procession at the command of the looming British officer.

Walter O. Evans Responds:

Walter O. Evans, president of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, formed the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art beginning with a portfolio of prints by Jacob Lawrence. A portion of the collection has been gifted to the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art.

The British attacked Washington, DC, on August 14, 1814, destroying the Capitol and White House. With instructions from First Lady Dolley Madison, fifteen-year-old enslaved Paul Jennings, manservant to President Madison, was able to save Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington and other treasures before the residence was burned to the ground. The British then moved on to Baltimore, where large numbers of both free and enslaved African Americans helped save the city. The soldiers at Fort& McHenry raised the American flag on September 13, after severe bombardment by the Royal Navy. It was this sight that inspired the slave-owning, antiabolitionist Francis Scott Key to pen “The Star-Spangled Banner,” a poem later adopted as the lyrics for the national anthem.

Enslaved African Americans did not fight exclusively for the United States. They were heavily recruited by the British, who promised them freedom in colonies in Canada and the West Indies. Ironically, at the conclusion of the war, enslaved African Americans who fought with US forces remained enslaved, whereas thos who served with the British were taken to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Trinidad as freedmen.

This outcome is not surprising when one considers the racist third verse of Key’s poem, which is never sung today: “And where is that band who so vauntingly swore, / That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion / A home and a Country should leave us no more? / Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution./

No refuge could save the hireling or the slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

/ And the star spangled banner in triumph doth wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.” The struggle for the rights to ”Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness″ for all African Americans continues.

Yoilett Ramos Sanchez Responds:

Yoilett Ramos Sanchez is a sophomore at Boston Community Leadership Academy. She lives with her two parents and siblings in Dorchester, MA. What matters to her most in this world is spreading love to others because she believes that in order to receive, you need to give in positive ways. In her spare time she likes to play with her nephews.

Panel 19 of Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle series shows four American men being held captive by British soldiers. The sailors are tied up tightly with thick black rope and are bleeding from wounds. The rich, red liquid that circulates in our arteries is running down their pants and skin onto the floor of the boat.

This must have been a traumatic moment for these men, standing in front of the British leader, whose posture reveals a sense of certainty: certain he is in control, certain what his next plan is going to be

He holds a sword which establishes his authority. In the background, you can see the backstay of the boat and the big sail. The leader looks at the sailors with disgust; the three thick black lines on his face near his eye, cheek, and nose indicate his age. His mouth is formed downward along with his eyes, which are nearly covered by his blue lid. I imagine the British leaders on the boat discussing how they will use the American sailors for their own benefit. This makes me think of the issue of the United States selling firearms to Saudi Arabia, leading them to target innocent civilians in Yemen. Forces in Yemen use child soldiers, and these children have no freedom of choice, just like the men in the picture.

It would be a lie to say I feel nothing toward this work. As a person of color, I feel like someone who has gotten revenge but feels bad about it later. In this painting, I am essentially looking at white people experiencing what they have been doing to my ancestors for centuries. I think about how in this case, it was done by their own race. How they felt to be captive. The men’s arms are bound so tightly by the rope that you can see they are turning blue.

But revenge is not what I actually feel because these men were held captive and made to feel inferior by their own race. Today, unfortunately, minorities often make each other feel inferior instead of uplifted; and we can’t make white people feel lesser, only they can. If white people experienced oppression among their own race, I am guessing they would feel this way. This thought creates an unfulfilled pit in my stomach. Marginalized people in the United States are giving white people what they want, which is to turn on ourselves. The question that comes up for me is, if white people turned on each other like people of color do, would everyone be equal?

How will you respond? Share your responses on social media using #AmericanStruggle