CONNECTED | Dec 12, 2025

Unpacking the accounts of a tea chest: From Madras to Massachusetts in 1801

Warning: This post discusses harmful and racist language that appears in historical materials in the Phillips Library collection. Read more about our approach to harmful language on our Digital Collections page.

Researching in the predominantly book- and manuscript-filled archives of the Phillips Library this summer, I was surprised to come across a tea chest. As I examined the lid, a gleaming golden inscription — almost invisible from certain angles — emerged from the lacquer finish, reading “奇种” (“rare cultivar”). The chest was gifted to the library in 2012, but dates back to the very beginning of the East India Marine Society and the founding of Peabody Essex Museum. As evidence of those founders’ trade in valuable tea from distant China, it is precisely the type of artifact they brought back to fulfill their mission: filling their cabinet of “natural and artificial curiosities.”

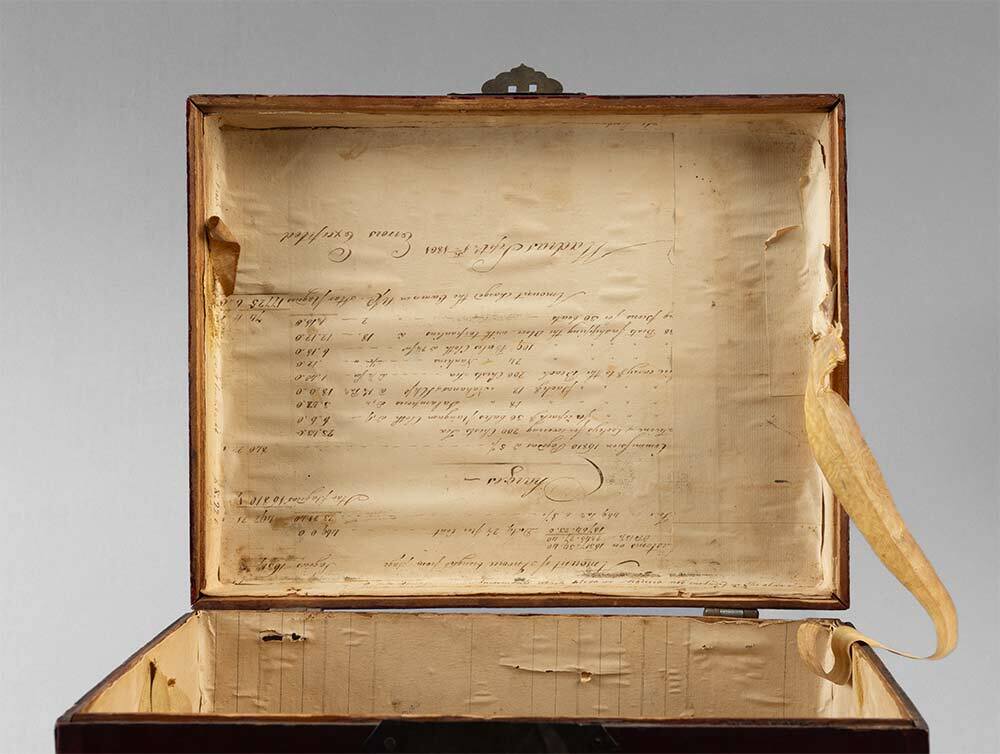

However, the tea chest is devoid of the rare contents promised by the inscription. Upon opening it, we find only six ledgers that line its lid, walls and base. Although these handwritten accounts led the chest to be catalogued as a manuscript, there are indications that the now yellowed and buckling pages were not applied with the intention of being read in detail; most notably, they are all pasted upside-down. I was immediately intrigued by what I might learn from reading this account that was not meant to be read. It soon became clear that these fragments could be pieced together to open onto histories of exploitation that the East India Marine Society merchants never intended to display.

Exterior of tea chest, 1801, MSS 835. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

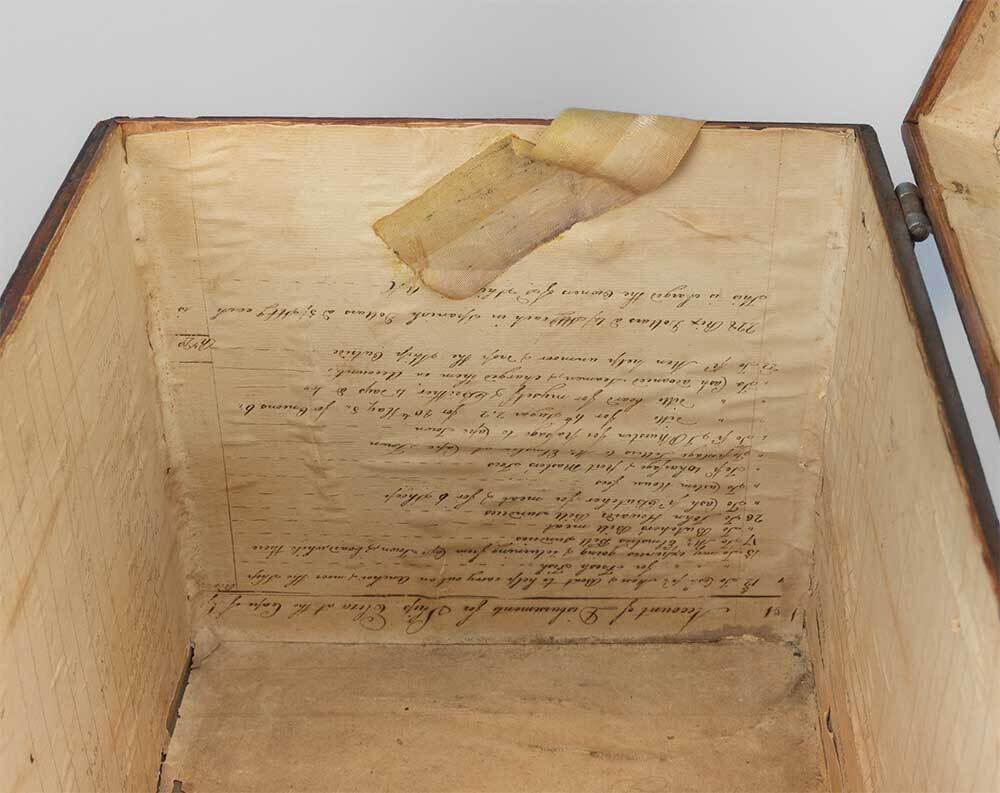

Upon opening the lid, the word “Madras” (present-day Chennai, India) is immediately apparent, scrawled in large print at the bottom of an invoice dated September 1, 1801. Looking down into the base of the chest, “Madeira” can also be found in the lower right corner and, tucked into the lower corner at the base of the left wall, “the Cape of Good Hope.” Finally, peering over the edge of the front wall reveals a list of familiar Massachusetts ports: Ipswich, Salem, Hingham, Newburyport, New Rowley, Lynn, Plymouth, and Beverly. Aiming to flesh out its scant text and material remains, I explored the chest as a small portal into American tea commerce and its global entanglements at the turn of the 19th century.

In 1801, Madras had a newly solidified status as a British colonial city following years of warfare that engulfed the region for much of the second half of the 18th century. Amid this near-constant state of warfare, the British East India Company fought continuously to expand its hold over South India. One of the first charges listed on the invoice pasted inside the chest is “Cooleys for covering 200 Chests Tea.” A derogatory term usually associated with coerced migration from Asia to the Caribbean, “coolie” was an ambiguous category under which Asian workers were racialized around the world.

Manuscript lining interior lid of tea chest showing invoice of charges from Madras, 1801, MSS 835. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

Closeup of document on interior of tea chest, 1801, MSS 835. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

Society under colonial governance was rife with unequal, brutal conditions for local workers, including coercion and corporal punishment. In 1797 the Madras Governor in Council officially invested the British port captain with the right to whip subordinates and to carry out “ritualized floggings […] repeatedly performed on the beach and other public places.” Such practices haunt us from between the lines of this invoice, which records payment for tasks that would have fallen under the supervision of the port captain: packing cargo, carrying it to the beach and ferrying it to ships in smaller boats.

Besides tea, the cargo listed on the invoice includes cotton textiles that had long been central to India’s economy. The textiles named on the invoice — “Pungum Cloth,” “Salampores,” and “Nakanas”— were broadly categorized as “Guinea cloth” after the "Guinea coast" that stretches from present-day Ghana to Equatorial Guinea. The term was used for cotton goods that sold well in the region, most characteristically woven with blue-and-white stripes or checks. European and American traffickers in enslaved people capitalized on the demand for Indian cotton piece goods in this long-established market. It is likely that this cargo was bound for West Africa, meaning the voyage of the tea and cloth from Madras was bound up with the transatlantic slave trade.

Cotton cloth doesn’t only appear in the chest’s writings: Holes worn in the paper along gaps in the wooden slats reveal tiny blue and white checks peeking out from the depths. Turning the chest over reveals that three strips of blue and white checked cotton were used to cover gaps in the wooden base. This casual repair using the very same type of cloth that facilitated the trading of human lives is a visceral reminder that enslaved labor formed the basis of the world economic order that emerged in the 19th century.

The library’s tea chest may have been bound for Massachusetts, but it illustrates how American merchants capitalized on the belligerent expansion of the British Empire. At the moment recorded in those pasted invoices, Britain had just taken control of Madeira and the Cape of Good Hope — ports the ship carrying this box would have utilized along its voyage. Like the chest itself, tea enjoyed in Massachusetts carried traces of the violences of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade.

The tea chest drew me in with its attractive patina and promising label, but over the course of my research, I was struck that, rather than being filled with treasures for display, the chest most notably contained absences: its emptiness, and the matter-of-fact ledgers that elide the human toll of American ventures in tea.

Blog

A Native American Fellow at PEM’s Phillips Library reflects on Native representation in library acquisitions

5 Min read

Blog

Ongoing effort seeks to identify and correct harmful terms in PEM’s library catalog

5 min read

Blog

Recent PEM acquisitions celebrate art across time and cultures

7 Min read

Blog

Graduate students dig into the papers of historic youth activists to tell the story of equal school rights in Salem

7 Min read