CONNECTED | Jun 17, 2025

Some choice morsels from artist billy ocallaghan

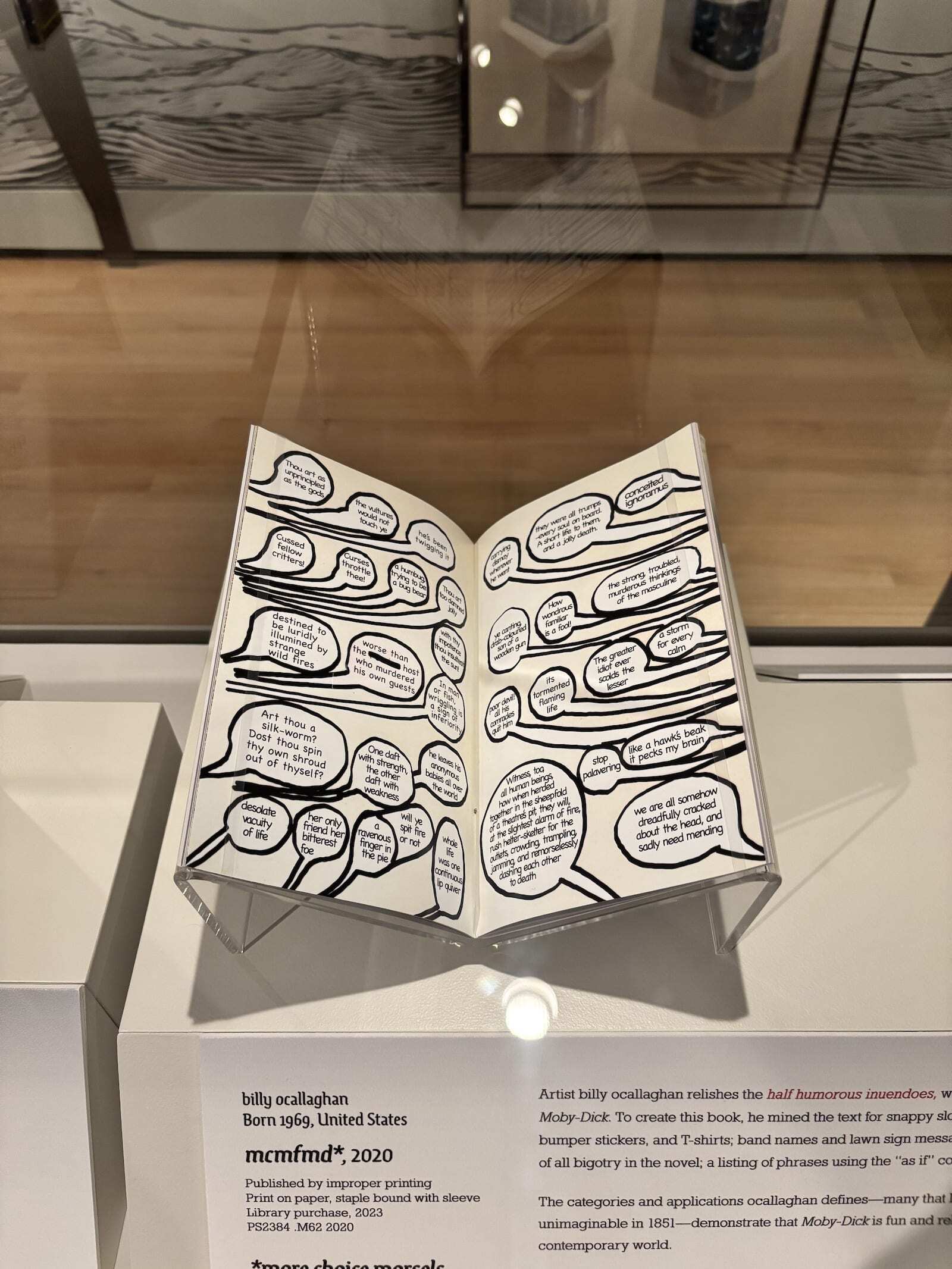

PEM’s exhibition Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick features a wide variety of reinterpretations of Herman Melville’s classic novel: some are serious, some are whimsical and some are somewhere in the middle. billy ocallaghan’s art book mcmfmd* *more choice morsels from moby dick brings the tale of the white whale into the 21st century by reimagining bits and pieces of it as slogans for baseball caps, bumper stickers and album covers. But ocallaghan’s work isn’t just quippy — he is also one of the many artists and scholars to spot the queer possibilities in Moby-Dick’s story and characters and consider them as a serious interpretation. billy ocallaghan (who formats their name without capitals to “suggest modesty and informality, the voice I want to speak with”) kindly answered our questions about tackling difficult books and queer representation in the arts.

How would you describe your work and yourself as an artist?

I’m a creative. I have an MFA from San Francisco State University, where my primary focus was zines and photography. As improper printing, I’ve published studio editions of 18 zines and 39 cascading accordions from my garage, plus 14 commercially printed zines and one hardback book. My self-published works are included in special collections libraries at 31 institutions, including 21 universities across 13 states. More recently, I’ve been working on creative writing projects, some of which involve video.

What other works have you redacted or remixed as part of your art practice?

My first-year project in grad school was a zine updating John James Audubon’s Birds of America. One side reproduces six of Audubon’s illustrations with the now-extinct birds redacted. The other side presents illustrations for 12 new birds, including Big Bird, Hand Turkey and Shadow Puppets. PEM has a studio edition of this zine in the collection.

Curator Dan Lipcan (the Ann C. Pingree Director of the Phillips Library) shows off one of ocallaghan’s hats during a chat with Maritime Art Curator Daniel Finamore. Photo by David Tucker.

Tell me about the first time you encountered Moby-Dick.

I started reading David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest — a great American novel of my generation — in the early 2000s. I gave up within the first 100 pages multiple times. In 2012, after completing my MFA, I started again with the intent to keep going. I also started trusting the author and anticipating that it would be more compelling once I got the hang of it, that maybe the next chapter would be more than enough to compensate for the occasional confusion and boredom. When I finished, I felt like I could read any book. I picked up Moby-Dick — another great American novel — in late 2013, reading it slowly and setting it aside as needed.

Early on, I was surprised to discover the queer content — the repeated use of the word “queer,” Ishmael’s relationship with Queequeg — and started thinking about making a zine to share my discovery that a great American novel was queer. I started marking the queer content in the book, and then everything else that interested me. When I was halfway through, I lost my marked-up copy of Moby-Dick. I waited for a few months, hoping it might turn up, and then started over. Beginning again with the queer projects in mind, the second time through the first half was so much more productive that I came to appreciate having lost the book in the middle of my first read.

billy ocallaghan, artist; improper printing, publisher. mcmfmd* *more choice morsels from Moby Dick, 2020. Ink on paper. Purchase, 2023. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum. PS2384 .M62 2020. © billy ocallaghan.

What inspired you to redact and pull “morsels” from the novel?

I redacted Moby-Dick to highlight the queer content in context. In part, I’m making a truth claim — Melville embedded a queer story in Moby-Dick — and using Melville’s words on the page helps support that claim in all its fullness.

I also marked everything else on the page that captured my attention, thinking I might make a B-side project for my queer Moby-Dick. I eventually evolved my notes into mcmfmd* *more choice morsels from moby dick. In part, I’m celebrating the breadth of ideas, and spectacular phrasing, that Melville wove into his book. I also catalogued the bigoted text and ideas that I couldn’t help but notice, including a full chapter on the alleged superiority of whiteness in nature. I struggled over how to address this. Should I stop working on the project? Do I want to spend more time and other resources lifting up a great book that also contained bigotry? Even though my heritage — Irish Italian — may not have been thought of as “white” at the time Melville wrote his book, I wasn’t personally subjected to the sharp side of that stick and do not believe I am finely tuned to notice or address it.

I also understand that our past is complicated and nearly all humans from the past would be found wanting according to contemporary standards, just as humanity may find fault with nearly all humans living today. I also believe we can draw out the positive elements without throwing away everything. My solution was to treat the bigotry like the other elements, creating two pages of highlights, and then redacting that text so that I’m calling attention to it without repeating the underlying ideas. I don’t know if this was the right approach but I do believe in grappling with the issue until we find better ways forward.

Part of my overall goal with this project is to model remixing of our cultural histories: We can all find the parts that speak to us and lift those up and/or critique them. The bigotry (redacted) pages are a placeholder and invitation for someone more capable to investigate and tackle those issues if they’re interested.

Why do you think queer people are sometimes driven to find representation in not-obviously-queer places, like classic literature and historical figures?

Growing up in rural California in the 1970s and 1980s, the overwhelming narrative was that queer people were bad, akin to criminals. This was buttressed with claims that queer people were a new, unnatural outgrowth of a hedonistic, sinful society. The ongoing erasure of queer history across cultures and time makes this kind of argument possible. Reestablishing the naturalness of queer — same-sex couples across animal species, queer figures across many historic cultures, queer content not-so-subtly hidden in classic literature and among historic figures — helps to rebut these baseless claims.

What does queer representation in museums (and galleries, and book fairs) mean to you? What do you hope for the future in that area?

Museums and libraries play many vital roles in our society. In part, they are keepers of the flame, ensuring that the art, artifacts and cultural histories that they’ve been entrusted with are accessible to their communities and survive into the future. In addition, they have the power to vouch for the importance and/or seriousness of the works in their care. For example, Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick has elevated my Moby-Dick zines from the self-published pamphlets that they are to be in dialogue with the book arts of Moby-Dick and book arts in general.

billy ocallaghan, artist; improper printing, publisher. mcmfmd* *more choice morsels from Moby Dick, 2020. Ink on paper. Purchase, 2023. Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum. PS2384 .M62 2020. © billy ocallaghan. Photo by Ellie Dolan/PEM.

Pages from the logbook of the Potomac featuring a tiny drawing of one of the deserters from the Acushnet (possibly Herman Melville) and an illustrated record of some of the whales taken by the ship. Log 495, Potomac (Ship) logbook, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Rowley MA.

How did your collaboration with the PEM Shop come about? Does making merchandise from and about your artwork add to mcmfmd* ?

I brainstormed various merchandising ideas with Dan Lipcan (the curator of Draw Me Ishmael) and Victor Oliveira (Director of Merchandising at PEM). Drawing from the ball caps pages of mcmfmd*, we decided to start with the hats. Victor asked if we should include a white whale on the back of the hats. PEM has a log book of the Potomac, a whaling ship in port when Melville deserted from the Acushnet, another whaler. The logbook included drawings of the sperm whales they encountered. We converted an image of one of those drawings into our white whale for the ball caps (and coffee mugs) — it’s wonky and feels more personal.

We’ve had some visitors come from as far as London just to see this exhibition — and your hats. Have you been surprised at the reaction to your work?

Yes — it has been amazing to see this project, which I dedicated years of my life to without any understanding of whether anyone would read and/or engage with it, be embraced by the broader world. It is wild to imagine folks traveling from London to see the exhibit and acquire some of the hats.

It’s surreal to have items I designed for the zine page be pulled into our reality as functional objects. It’s a joy to see them around my house, to have them to wear and share with friends and, through the PEM Shop, the broader world.

Did you have any favorite works by other artists in Draw Me Ishmael ?

I’m fascinated by Ricardo Bloch’s collage/comic remix Huckleberry Dick and have added it to my own collection of artist books.

You can learn more about billy ocallaghan’s work at improper printing, their California-based press for zines and cascading accordions (which the artist describes as “small, hand-folded books that animate when played, somewhat like a flipbook crossed with a slinky.”) Pick up a limited-run copy of the mcmfmd* zine in the PEM Shop.

The museum has another exhibition that includes the work of LGBTQIA+ artists debuting this month: Making History: 200 Years of American Art from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, opening on June 14. You can also learn about our June programming for the queer community at pem.org/pride.

Draw Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick is organized by the Peabody Essex Museum. This exhibition is made possible by Carolyn and Peter S. Lynch and The Lynch Foundation. We thank Jennifer and Andrew Borggaard, James B. and Mary Lou Hawkes, Chip and Susan Robie, and Timothy T. Hilton as supporters of the Exhibition Innovation Fund. We also recognize the generosity of the East India Marine Associates of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Related posts

PEMcast

PEMcast 36: The Book Arts of Moby Dick

30 Min Listen

Blog

Ongoing effort seeks to identify and correct harmful terms in PEM’s library catalog

5 min read

BLOG

A group of Salem friends dives into Moby-Dick, slowly

7 min read

PEMcast

PEMcast 31: Queerness and Creativity

24 min listen