As PEM’s Chief of Security, Facilities Operations and Planning, Bob Monk has been living between two worlds.

His 12-hour days require a focus on present needs at the museum, such as keeping artworks and empty buildings safe, while overseeing maintenance projects. But his attention never strays from the future and formulating a plan to safely open to the public.

Monk was instrumental in opening PEM’s new wing in September 2019 and then was on to the next project — creating a master plan for PEM's campus. But the global health crisis created a total pivot. “The objective right now is to get through the pandemic,” Monk says. “Right now the focus is on righting the ship.”

While facilities and security people are used to being in the museum when things are closed, a totally empty space on a sunny spring day certainly feels strange, says Monk. “You can walk through a gallery and feel privileged to have the whole place to yourself with beautiful and compelling objects. But that very quickly becomes overshadowed by loneliness and sadness. You can turn all the lights on — all the way up — and the place just isn't as bright without people.”

What he wants more than anything, says Monk, is the place full again, of toddlers for PEM Pals on Wednesdays and visiting school groups coming in from all over. “But you can’t think like that without realizing that there could be a real danger in that,” he says.

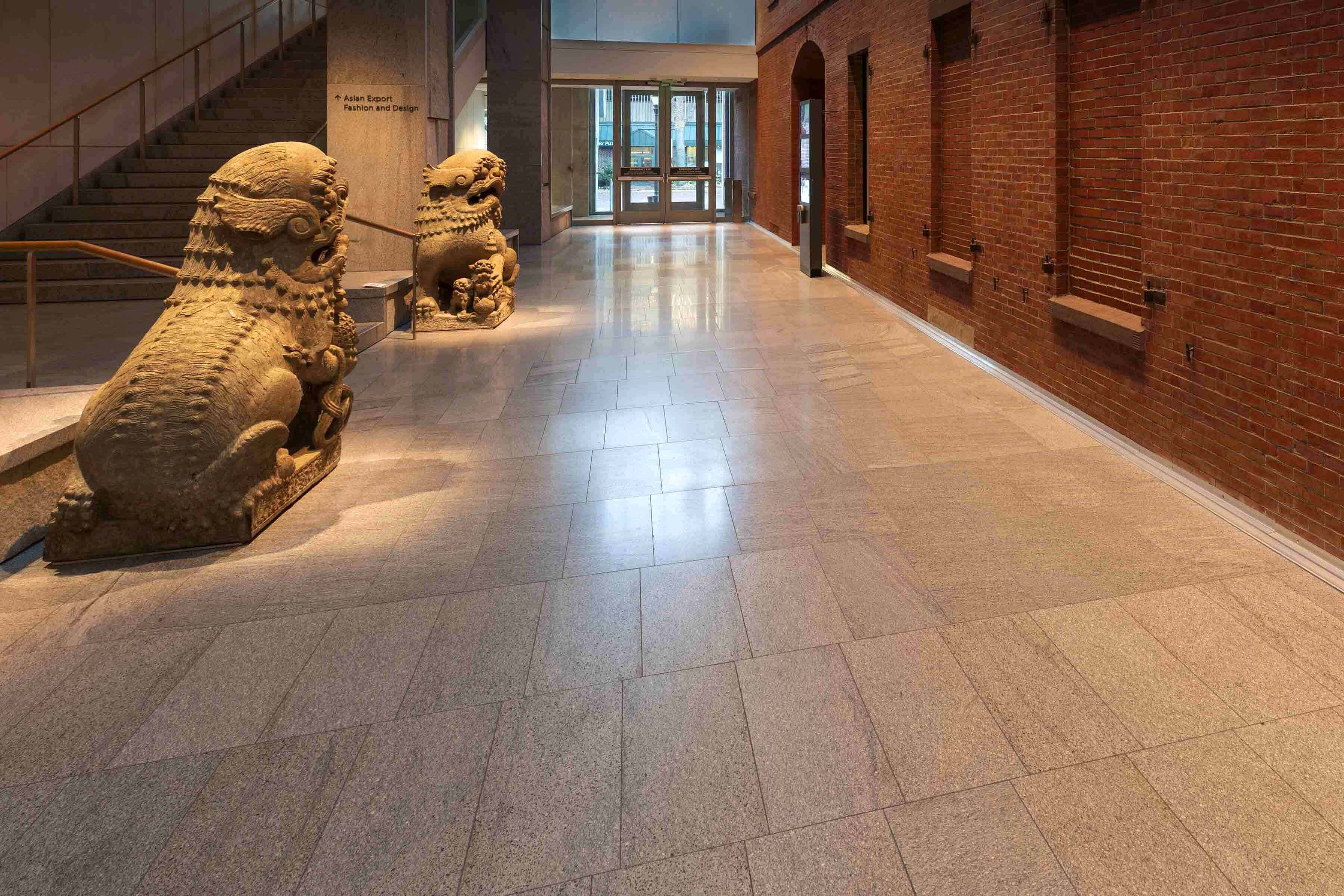

Photo by Bob Packert/PEM.

"You go right back to — how do we make this place safe? We all thought that closing the museum was going to be difficult. After a few days, you realize that was the easy part. Getting it open safely is going to be hard."

In the course of a career in facilities operations, dealing with some sort of disaster is inevitable, says Monk, who has been at PEM for 21 years. But no one could prepare for how different life would be in the spring of 2020 with a pandemic. The museum world has been having an ongoing conversation about limiting the number of people in a gallery, the handling of ticket sales, sanitation protocols and masks required at all times.

While the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston was first to open in the U.S., PEM hopes to reopen this summer, which means Monk is on video conference calls with PEM’s leadership and leaders of other regional museums, sometimes for several hours a day. He was featured in this Boston Globe story that focused on strategies for opening museums in the area.

After 11 weeks of closure, Monk and I chatted about those who were not able to work from home — the 30 people who still showed up to work at the museum during closure. I followed up with three of them:

Security Guard Tina Emmith

Though each identical day can feel like the movie Groundhog Day, says Security Guard Tina Emmith, she has felt grateful to have a place to go during the health crisis. She can’t wait for a day that feels different — when the rest of the staff and the guests join her at the museum.

Moments that stand out in her 15 years at PEM are a food event called The Art of Taste Event with Siddhartha Shah, Curator of Indian and South Asian Art, where she met Ted Allen from the Food Network show Chopped and celebrity chef Maneet Chauhan. She also loved the Pride dance party last June.

A fan of PEM’s Asian Export Gallery, Emmith says that while being in the museum over the last few months she has observed: “The objects just sit in the dark. They have a story to tell. We need to light them up and emit some positive vibes.”

One thing that has been glowing lately is Emmith’s favorite object at PEM. Kū is a temple image from Hawaiʻi that has been in the collection since 1846. When the front of the museum looked dark, PEM’s master electrician shined a light on Kū, visible from the street.

Master Electrician Henry Rutkowski

“Early on I lit him, so he could bring hope,” says Henry Rutkowski, PEM’s Master Electrician.

Henry Rutkowski. Courtesy photo.

Looking back over his 17 years at PEM, Rutkowski recalls meeting icons like world renowned cellist Yo Yo Ma and rock star Kirk Hammett. “Kirk Hammett called me a ‘lighting surgeon,’” he says, relaying what had to be a career high. Of all the works at PEM now, Rutkowski especially loves Charles Sandison’s installation in East India Marine Hall, with its projected 19th-century ships and captain logs covering the walls and ceiling.

One of the things Rutkowski is looking forward to is his hobby as a Revolutionary War reenactor, calling it his “release from reality.” His two worlds converged one year when in October his group of costumed players had the pleasure of sleeping on the lawn of his favorite PEM historic property, the Crowninshield-Bentley House.

In the meantime, Rutkowski has been putting in long days, upgrading the museum’s lighting systems. His daily routine consists of making sure his son does his home-schooling and going by Ziggy’s, the family donut shop on Essex Street, for his morning coffee before punching in at 8 am.

There is no doubt that Rutkowski is a social creature, eager to see his colleagues again. “It is too quiet,” he says, “and very sad not having guests or colleagues around.”

Lead Security Supervisor Kevin Hudson

“Walking through sometimes all you hear is your own footsteps and the occasional jingle of your keys,” says Lead Security Supervisor Kevin Hudson. Hudson is helping prepare things for when some staff return to the museum’s offices again. A long list of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines must be followed for 25 percent of workers to return this month. “That real face to face interaction has been greatly missed,” says Hudson, who started at PEM in 2001 while in college.

Kevin Hudson. Courtesy photo.

It’s hard to believe that just nine months ago, the new wing opened, with “energy and enthusiasm,” says Hudson, whose daughter was one of the lucky kids who helped christen the new School Groups Entrance during opening celebrations.

When asked what he has enjoyed on PEM’s campus during closure, Hudson says, “I've always had a soft spot for our historic homes … Even the museum building itself is an amalgamation of building upon building built over time, each with their own story to tell.”

As staff members slowly begin to return to the museum offices and plan for the reopening of the museum, Monk reflects on one object in the maritime gallery that he could identify with during these quiet months of closure.

“One thing that signifies isolation more than anything is the calendar stick,” he says, referring to a stick a sailor, remarkably named James Drown, used to mark time after an 1804 shipwreck marooned him on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. “We’re not subject to all the hardships that fellow was … 126 days or something like that.”

Actually, it was 161.

“I forget all the notches that were in there,” says Monk. “But we’re coming close.”

Keep exploring

PEMcast

PEMcast 13: #newpem

10 min listen

Blog

Embracing PEM once again

10 min read