CONNECTED | Oct 01, 2025

Behind the scenes of Nosferatu at PEM with Arpeggione Ensemble’s co-director

“Listen to them, the children of the night. What music they make!”

Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula is one of the most frequently adapted works of literature in the world. From Bela Lugosi to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the influence of Stoker’s most well-known work permeates modern-day horror and suspense through books, plays, movies and television. PEM audiences will soon enjoy a classic Dracula adaptation for the silver screen with a live performance by Arpeggione Ensemble on October 25.

At the height of their popularity, silent movies weren’t silent: Audiences experienced a film with a live orchestra playing along in the theater, or at least an organist or pianist. Every moment of terror, romance or sadness had an accompanying musical mood, along with sound effects like bells and birdcalls on some theater organs. Arpeggione aims to recreate the excitement of this era with our historically accurate scoring of F. W. Murnau’s German Expressionist film Nosferatu: Eine Sinfonie des Grauens, which premiered in Berlin on March 4, 1922.

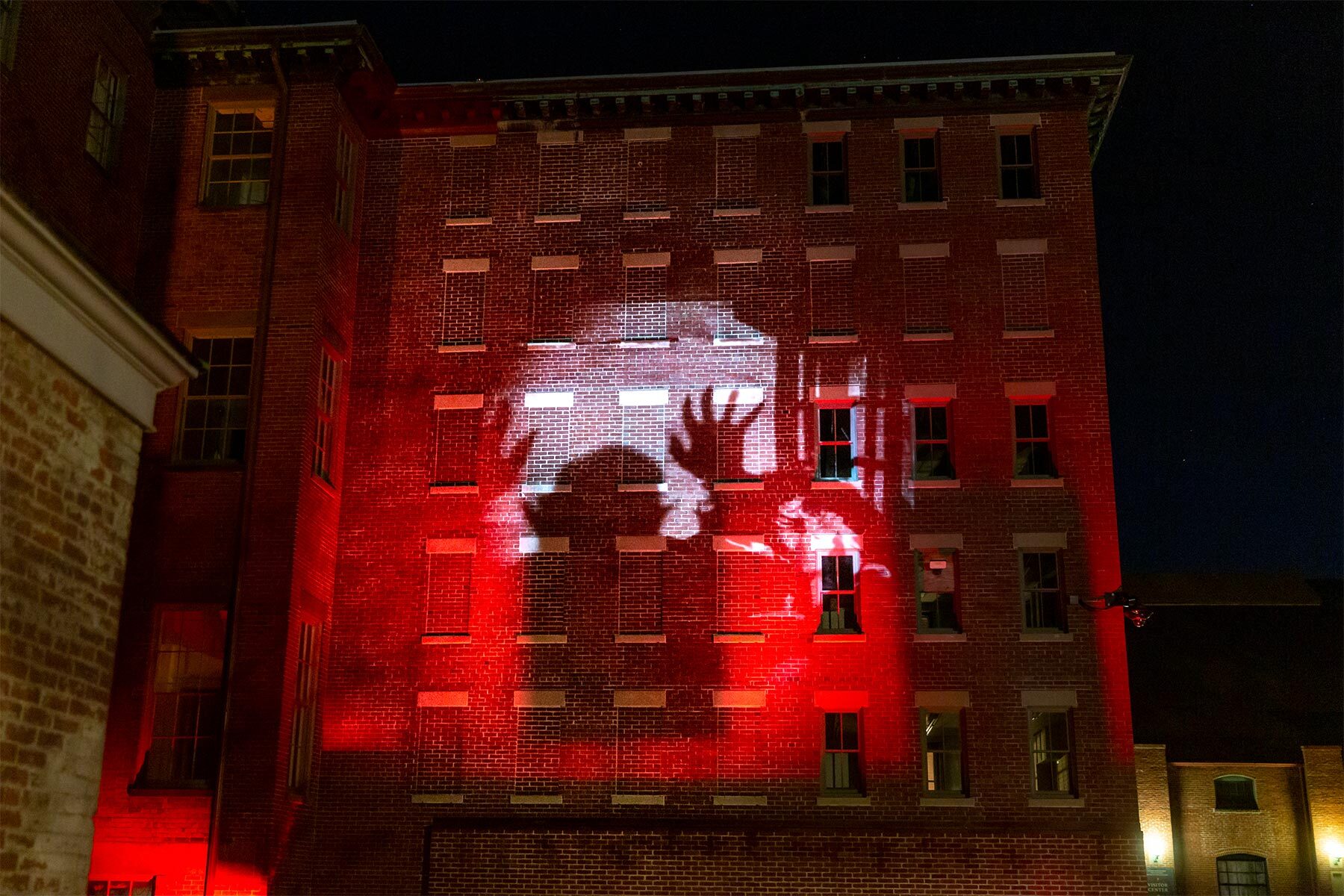

Image courtesy of Arpeggione Ensemble

The original Bram Stoker Dracula has always appealed to me because of the strength of the writing. It’s epistolary (written in the form of letters), so not every character is getting the same information at the same time. The suspense is even stronger, because as readers, we know what is going to happen before almost every other character aside from Dracula himself. Stoker had a very good grasp on theatrics and the people in and around the theater, and it comes through in his writing, which feels tailor-made for visual consumption. I think that’s why so many studios and directors have adapted the novel to film and other media over time.

Nosferatu is the earliest film adaptation of the Dracula story. While the narrative is more or less intact, due to issues of copyright and obtaining the rights to Stoker’s work, the Prana film production company changed certain elements of the plot in order to avoid a legal battle. These alterations included changing the setting of the film to Germany, combining the roles of several of the characters and omitting the climactic battle at the end of the novel in favor of a more emotional (and cinematically achievable) ending. The names of all of the characters were also changed, with Jonathan Harker and Dracula becoming Hutter and Count Orlok. The title of the film comes not from the title of the villain, but most likely from an ancient Romanian word for “offensive.” Today, we can retroactively view the film as a critique of xenophobia — but we unfortunately know how history unraveled.

From the eerily corpse-like appearance of Max Schreck as Orlok to the oft-parodied staircase shot at the film’s climax, Nosferatu set the standard for the modern horror movies as well as the genre of vampire films. Interestingly, several of the most enduring aspects of vampire lore come not from Bram Stoker’s pages, but from Murnau’s film adaptation. The Dracula of the novel openly walks in sunlight, while Count Orlok must avoid it at all costs.

With our live performances of the score of Nosferatu, I think audiences can expect to see and hear the film in a completely new light. I’ve been living with this score in my brain for more than two years now and even I was blown away conducting it in rehearsal for the first time with the film, and seeing how much I could play around with the musical material to highlight the action on the screen. There’s also something so vibrant and organic about feeling the vibrations of live music as you’re watching a movie — an experience that moviegoers regularly had in theaters during the silent film era. I feel like as a society we’ve been fed packaged and perfected music all our lives, so listening to live music where anything can happen really feels like a shock to the system.

The score Arpeggione plays from is a bit of a pastiche of sources. The original score for Nosferatu’s Berlin premier was composed by Hans Erdmann, but that score is lost. The only published material remaining is a keyboard reduction of the various themes with the designation “Für Film und Schauspiel” (“For film and stage play”) but with very clear directions on how each theme was to be played to fit certain moods, and in some cases with instrument suggestions penned in. Reconstructions have been attempted over the years, the most “complete” by Gillian Anderson and James Kessler in 1995 — but this score was written for a large modern orchestra, not a small early 20th-century theater orchestra.

Image courtesy Arpeggione Ensemble

In keeping with many of the conventions of 1920s theater orchestras, Arpeggione’s score sketches rely heavily on the use of keyboards (harmonium and piano) to substitute for additional instruments such as the oboe that might not have been available to a particular theater. Consulting both the surviving source music by Erdmann and the modern reconstruction, we have reimagined the score for performance by a 1920s theater orchestra. You might also catch a glimpse of various members of the orchestra doubling on percussion at certain points in the film, as they might have during that time period!

Our ensemble plays on a variety of historical instruments from the beginning of the 20th century. Our harmonium player George Wiese is one of the foremost experts on the harmonium and its history. For previous Nosferatu performances, he played an instrument that would have been almost an exact match for the harmonium used in Berlin at the premiere, down to the year. The string players are performing on a mixture of gut and steel strings — totally appropriate for the time before orchestras switched to all metal strings later in the century — and the wind players are all performing on original instruments from the turn of the century. As a clarinetist, I feel there’s something special about being able to use an instrument from the 1920s to play music of that time period, because the instruments do respond differently. The fingerings are slightly different, which opens up a new world of tone color. The mouthpieces are made of wood and not hard rubber, so there’s a more lyrical and organic sound, and the instruments all seem to blend together more easily. It’s a wonderful experience.

Just like spoken and written language, music has evolved and changed over the years and certain stylistic traits have changed dramatically over the centuries. I find that learning to become fluent in all of those stylistic eras adds a layer of depth to historical performances, where the composer and their musical language are highlighted in addition to the skills of the performer. I’m also an equipment hound, so any area of music that means I can also collect, restore and build musical instruments from a certain time period is an automatic draw for me.

I think the 1922 Nosferatu has always been popular, but in a cult-following sort of way. We’re living amid a rise in popularity of Nosferatu screenings with live music: I think there are more theaters and venues willing to take a chance on incorporating live music for screenings, whether it’s organ improvisation, modern electronic music or, as we’re doing, a reconstruction of Erdmann’s score. (Interestingly, Hans Erdmann literally co-wrote the book on film scores in 1927: He explains how to score a film, and what type of music should be used during certain dramatic and emotional moments. We learned a lot by poring over the book and getting inside Erdmann’s head with his own dramatic suggestions.) Even the subtitle of Nosferatu is “A Symphony of Horrors.” It’s very clear that Murnau thought of music, whatever that meant, as an integral part of this film, and Erdmann’s music is an absolutely brilliant time capsule of 1922.

Join the Arpeggione Ensemble and co-director Thomas Carroll for two screenings of Nosferatu with live music at PEM on October 25.

Related posts

Blog

Mediums, Magicians, Makers and the Objects Used to Conjure Spirits

8 Min read

PEMcast

PEMcast 19: The Legacy of Salem's Witch Trials

25 min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 1: Music

22 min listen