In this episode of the PEMcast, we examine the life of one of America's most famous 20th century painters who you may not know.

Thomas Hart Benton captured the heart of Curator Austen Barron Bailly. The hosts trace the artist’s life and talk with Bailly about his productive time in Hollywood. We also talk with the art handlers traveling with the works and a passionate private collector.

[INTRO MUSIC and voiceovers from Austen Barron Bailly, PEM’s Curator of American Art, Edward R. Murrow from an interview recorded in 1959, and Rob Lezebnik, a writer for The Simpsons:]

Austen Barron Bailly, Curator: I think I just found his works so bold, so ambitious, so idiosyncratic.

Murrow Recording: Rugged, outspoken and unconventional.

Rob Lezebnik: You know, his style is so dramatic and has so much energy to it, that I was sold.

Austen: He really couldn’t go anywhere without being recognized, he received fan letters, people wanted his autograph…and then, things changed.

Host, Chip Van Dyke: Welcome to the PEMcast. Conversations and stories for the culturally curious. This is Episode 005. My name is Chip Van Dyke, and with me as always is…

Host, Dinah Cardin: Dinah Cardin.

Chip: With another big exhibition opening in a few days, we’re pretty busy here at the museum. The entire staff is all hands on deck. And, Dinah, I’m sure it’s probably no different for you over in the Public Relations Department.

Dinah: Yes, in PR, we’re up in the galleries all the time now with the press, giving them special access to our curatorial staff and to the artworks so they can write their reviews. And so far, they seem to like it.

Chip: Getting these shows off the ground is always an epic journey, and, as of this recording, we are really close to the finish line. But let’s take a few steps back to just a few days ago, when the paintings were just being hung.

[AMBIENT GALLERY SOUND, VOICES]

Chip: We’re standing in a large gallery that’s currently under construction. This isn’t a sight that a lot people get to see. There are lighting technicians on very tall lifts, pointing lights down at paintings. There are Collections professionals uncrating artworks and filling out detailed condition reports. There are speakers and projectors being hung and positioned. And in the middle of all this activity is our curator for this show, Austen Barron Bailly.

Austen: Benton’s style is very distinctive. It’s very difficult to mistake a Benton because of its very dramatic, high-contrast modeling…

Dinah: American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood is the first major show on American artist Thomas Hart Benton in more than 25 years. It’s also the first to explore connections between his artwork and the movies.

Austen: This painting in the exhibition, People of Chilmark, really announces Benton’s emerging cinematic style. So the grand traditions from art history, motion picture production technique, big scale, bold colors, dramatic poses -- all of this comes together in a painting that depicts ordinary Americans from Chilmark, Martha’s Vineyard, his friends and acquaintances on the island where he ended up summering for over 50 years.

Background voice: Wow, that’s really complete.

Austen: [LAUGHTER] That’s a backstory, if you will.

Chip: In preparation for this exhibition, museum-goers were surveyed informally on their knowledge of the artist. The survey shows that only one in four people have even heard of Thomas Hart Benton. And I have to confess to you, Dinah, I’m definitely one of those people that didn’t know about Thomas Hart Benton, and I went to art school and took art history classes.

Dinah: And I am the exact opposite. I’ve known about Benton for most of my life. He was this larger than life character. He grew up about an hour away from where I grew up, in the Missouri Ozarks. Except, of course, about a century earlier. I was just recently visiting the Ozarks, and everywhere I went, I told people about this upcoming exhibition, and they all had a Benton story to tell. One night I jumped in a taxi with some friends, and the cab driver starts talking about him, and then somebody else said, “Oh yeah, I know someone who has a lot of Bentons.” I mean, everybody there, they just get wistful, and they love him, and they’re very proud of him.

[MUSIC INTERLUDE]

Chip: So today we present to you one of America’s most famous painters who, according to a survey, 75% of you have never heard of.

Dinah: And if you’re one of the 25% who are aware of Benton’s work, stick around. Because like me, you’ll probably learn something new.

[MUSIC INTERLUDE]

Female Recorded Voice on Tape: And now back to Ed Murrow.

Ed Murrow: Thomas Hart Benton has been described as America’s best-known contemporary painter.

Chip: Edward R. Murrow interviewed Thomas Hart Benton on his show Person to Person in 1959. Murrow, as you may know, was a TV personality who had the opportunity to interview the likes of Frank Sinatra, John F. Kennedy, Fidel Castro…the list goes on.

[MURROW AND BENTON ON TAPE:]

Murrow: “Good evening, Tom.”

Benton: “Good evening, Ed.”

Murrow: “How are you?”

Benton: “Pretty good.”

Murrow: “Tell me, do you have any plans to celebrate your birthday next Wednesday?”

Benton: “Well, plans are being made….”

Chip: At the time of this interview, Benton is days away from celebrating his 70th birthday. This interview is certainly not his big debut in the spotlight. Far from it.

Austen: He did these major mural series for the Whitney Museum of American Art, then in six months he completed a 250-foot long mural for the state of Indiana, and then Missouri commissioned him to decorate the house lounge at the Missouri State Capitol. He got paid more money than the governor. He was on the cover of Time magazine in 1934, and then he was off to Hollywood in 1937, and working with John Ford and 20th Century Fox and, you know, Oscar-winning pictures like Grapes of Wrath.

Chip: So, just how did he get here? As a young man, he studied art at the Art Institute of Chicago, and then he moved to Paris to continue his studies. After that, he moved to New York to continue painting.

Dinah: Benton travelled the country by foot, bus and train, in search of subjects to draw and paint. Often without an itinerary or without telling anyone where he was going.

Austen: Benton did, in his travels around America, seek out the kinds of individuals who could represent American types that could tell authentic American stories.

Dinah: Benton painted what he saw: the factory workers of the North East, the cotton pickers of the Jim Crow South, the displaced Native American tribes in the Wild West.

Austen: Benton is unafraid to look at the strengths and weaknesses in American character.

Mary Schafer: Some of the paintings in this exhibition are difficult to look at.

Dinah: This is Mary Schafer, a conservator with the Nelson Atkins Museum in Kansas City.

Mary: But I think that that’s what makes a Benton show. I mean, he didn’t just paint pretty pictures.

Dinah: Mary points to a painting hanging close by, titled The Minstrels. It depicts black musicians and actors performing on a hastily put together stage. Two of the four performers are in black face, the only audience a group of six young white men in the front row.

Mary: Are they enjoying the show? Like, is this kind of a creepy scenario? You know, that’s kind of a tough subject matter. For me.

Dinah: Mary spent hours and hours going through the Benton paintings in our galleries here at PEM.

Mary: My role here is to examine each painting when it comes out of its crate and check its condition and document its condition so that as these paintings continue on for the next three venues, I can monitor and ensure that their condition remains unchanged. So this is day 18 or 19 of examining Bentons. So far I haven’t had any dreams of Benton paintings, um, but there’s still time.

Chip: In 1937, Life Magazine sends Benton off to Hollywood on assignment. The assignment was to capture the glitz and glamor of the burgeoning Hollywood scene. Instead, the artist finds himself drawn to smoke-filled meetings and behind-the-scenes glimpses of the props department, which wasn’t quite what the magazine editors were hoping for.

Rob Lezebnik: I mean, I think it sort of sums him up. He looked at this entire industry in Hollywood and he reduced it to something sort of scandalous and base, and he, you know, was poking his finger in the chest of it.

Dinah: This is Rob Lezebnik, a producer and writer for The Simpsons. Rob grew up in Missouri and is a huge fan of Benton.

Rob: I think I was about ten years old, and my parents dragged me to the State Capitol in Jefferson City, which is maybe an hour from my hometown of Columbia. And I thought this is going to be the most boring day of my life. And then we walked into this gallery, and, uh, saw these incredible murals that Benton did for the State Capitol. There are scenes depicting Missouri history, including Jesse James’ gang and dancing ladies on stages, and I think a guy killing a cow with a hammer. And, you know, to a kid this was all just like...it was amazing. I think it was the first moment which I thought, wow, art can be actually kind of cool. And so I loved it.

Dinah: Rob wrote a pretty entertaining essay for the Benton exhibition catalog in which he refers to this statement from the artist: Benton, quote, “wanted to give the idea that the machinery of the industry – cameras, big generators, high-voltage wires – is directed mainly toward what young ladies have under their clothes,” end quote.

Chip: One of the reasons we were in contact with Rob, on top of the fact that he’s a very funny writer, is because he actually owns a graphite sketch that Thomas Hart Benton drew while he was in Hollywood.

Rob: My wife and I were at an art fair in LA, and they had a bunch of Benton drawings. And this one great pencil drawing jumped out at me. It was this middle-aged guy who’s kind of overweight and he looks pretty full of himself. And he’s on this crazy phone; I don’t even know what it is exactly. It’s connected to this huge kind of switchboard. And he’s got a cigar in his mouth or in his hand, and he just looks very self-satisfied, and I kept coming back to it. I kept kind of thinking that it would be ridiculous to actually spend this much money on something, but, um, you know I had this little history with Benton and Missouri, and I’d never known that Thomas Hart Benton had come to Hollywood, so all this was a perfect triangulation of events for me, and I probably should buy this. So I did, we took the leap, and I love it. I’m glad. I look at it every day.

Dinah: Where is it? Is it in your office?

Rob: No, it’s actually right in the front of the house when you open the door, and, uh, it’s the first thing you see in our house. So it really has a place of honor on our walls.

Dinah: Actually, it’s not there right now. The drawing is part of our exhibition. Rob was kind enough to lend it.

Rob: I particularly like that Benton titled it fairly sarcastically Young Executive, because the guy is certainly not young. Even though that’s 80 years ago almost, I still kind of know this type of guy, and I feel like I’ve tried to sell projects to him, and I’ve had ideas rejected by him, and I just like that he’s a constant in my world. I think it speaks to Benton’s sense of humor and, uh, his irony and his disdain for probably a lot of people, but certainly for this guy.

[MUSIC transitions to voice on recording]

Male Voice: A great American artist, Thomas Hart Benton, portrays World War number two. He explains his war paintings with: Benton on recording: I made these paintings because of a conviction obtained by traveling around the country to lecture during the weeks following Pearl Harbor. I saw that too many people were over-confident, over-optimistic, and under the impression that their lives could go on much as usual while George won the war.

Austen: The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Benton’s on a lecture tour, he drops everything and starts painting in the most visceral, vitriolic way in response to what he calls “the year of peril.”

Chip: And while Benton brazenly painted World War II, one of his young students from the Art Students League of New York was just beginning to find his voice.

Recorded Voice: My opinion is that new needs need new techniques. That the modern artist has found new ways and new means of making his statement.

Chip: Jackson Pollock.

Jackson Pollock: It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express this age – the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio – in the old forms of the renaissance or of any other past culture. Each age finds its own technique.

Dinah: Before he was known for his drip paintings, Jackson Pollock was Benton’s protégé and painted a lot like him.

Chip: It was only later that Pollock parted ways with his mentor’s style, and while Benton focused on the techniques of old world masters, the critics focused on Pollock.

Austen: Once Jackson Pollock and abstract expressionism started to rise, he really fell somewhat out of favor.

Chip: It’s not as though the world turned its back on Benton. Many Americans still adored him, and maybe that’s why Dinah’s experience with him and mine are very different, why one person out of four can recognize the name Thomas Hart Benton. In Edward R. Murrow’s 1959 interview with Benton, Murrow asks him to evaluate the current state of the art world. You can tell by Benton’s response that it’s probably not his favorite topic.

Benton: The great artists, that is, the highly publicized artists of this day – they’re entertainers rather than creative artists. They’re inventors of various kinds of entertaining gadgets. I really think that the artist has all this century tended to run away from any kind of meanings…

Austen: The dominant critical perspective in the art world in the mid-20th century was on the abstract expressionists, on the color field painters. Benton represented everything that they were not. And it has taken, you know, a good forty years for a new generation of scholars that I represent to come at Benton’s art from some very different perspectives.

Dinah: Back in her office, Austen prepares for the numerous programs and events that surround her exhibition’s opening. She flips through the exhibition catalog, and stops on a particular painting.

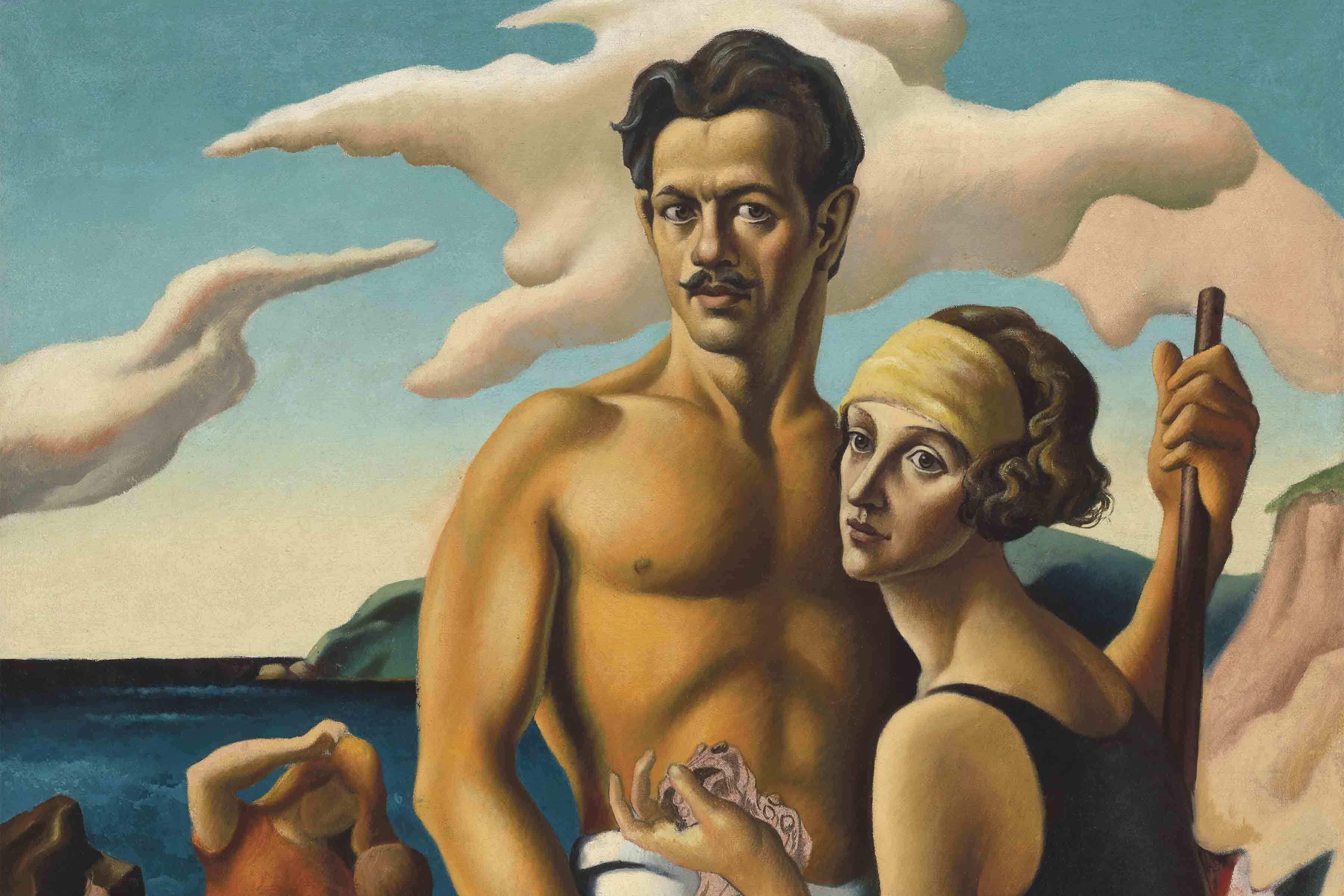

Austen: I really do love his Self-portrait with Rita. The painting has the look of 16th-century Mannerist canvases, which he loved and studied really deeply, but it also has the flare of a kind of movie poster. Is he, you know, a movie star with Valentino-like mustache and hair, and his bare chest and his beautiful wife Rita like a co-star by his side on a Martha’s Vineyard beach. And he’s wearing this timeless signifier of a faceless wristwatch, which to me is this really powerful symbol that he is part of this continuum of art history and he is a new leading man for American Art, a new kind of modern American Art.

Chip: Benton continued to work right up until his death in 1975. He died putting the finishing touches on a painting for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville.

Dinah: Even though his paintings sometimes depict an exaggerated place, full of characters we only wish we’d known – the bootlegger, the starlet, the gangster, the jazz musician – they still have the power to take us to real places. The cotton fields, the sultry South and to Hollywood in its heyday.

[MUSIC INTERLUDE]

Chip: American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood is at PEM through September 7th, 2015. It then travels to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth and the Milwaukee Art Museum in Milwaukee.

Dinah: That’s our show for today. Thanks for listening. Remember to find us on iTunes, Soundcloud and any podcast app. If you have questions, comments or stories to share, please write to us at our email address, pemcast@pem.org. Find more content related to this episode on our blog connected.pem.org. While you’re there, you’ll also see a blog post by Thomas Hart Benton’s daughter, Jessie Benton. She writes this loving tribute to her father and talks about his work in Hollywood, which led to her rubbing elbows with celebrities like Burt Lancaster and Marlon Brando. We’re pleased to share with you that the American Alliance of Museums has awarded the PEMcast a silver Muse Award in the category of Audio Tours and Podcasts.

Chip: Congratulations to my alma mater, RISD, for grabbing the gold for their museum audio series titled, simply, Channel.

Dinah: In the meantime, we’re working on our next episode, which includes stories from the outdoors. ‘Til then.

[END]

Keep exploring

PEMcast

PEMcast 23: Postcard from Crystal Bridges

25 Min Listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 15: The Struggle

13 min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 18: Alterations

14 min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 28: Drawn to Place

37 min listen