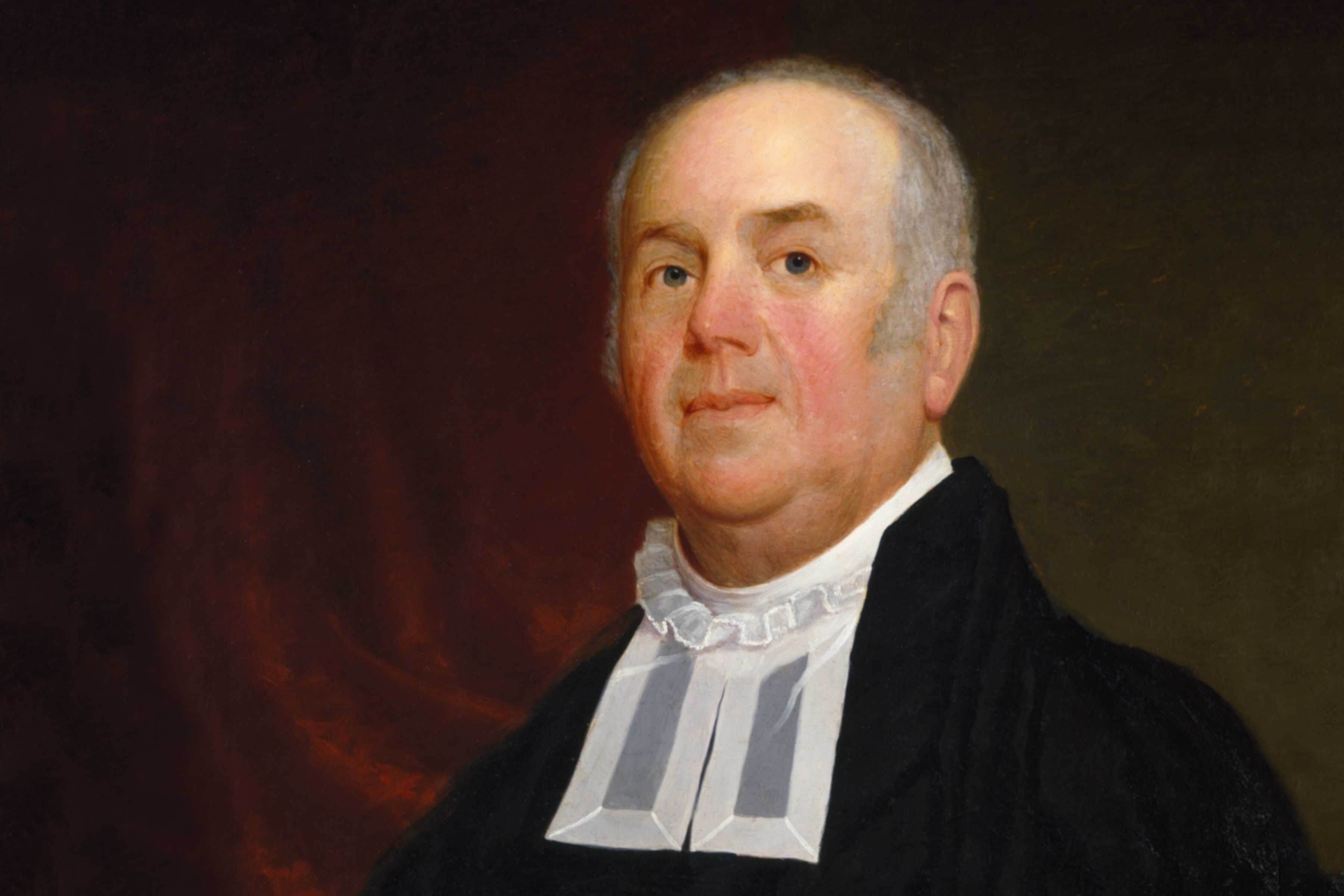

ABOVE IMAGE: James Frothingham, Portrait of the Reverend William Bentley, early 19th century. Oil on canvas. Gift of Lawrence Waters Jenkins, 1936. M4474.

It’s 1799: Salem is one of the largest cities in an emerging country. Its ports bustle with ships from around the world.

Salem’s fleet included the first American vessels to enter many Eastern ports. Mariners left Salem loaded with timber and dried fish, only to return months later with black pepper, tea and spices. Back home on Derby Street, shop windows displayed elegant women’s clothing, books and table linens from faraway lands. Sailors gathered together on corners and in taverns to share knowledge of distant cultures and show off souvenirs of the places they visited.

And keeping track of all of it all was one local Unitarian minister. The Reverend William Bentley kept a meticulous diary that now opens a window to 18th- and 19th-century Salem, complete with scenes from its busy port and key moments in a new nation.

In Part 2 of this episode of the PEMcast, we continue looking at the remarkable and storied life of Reverend Bentley. With Ruthie Dibble, PEM’s Robert N. Shapiro Curator of American Decorative Art, we explore Bentley as an early American collector, diving deep into one object: the oldest sundial brought to the Americas by the English.

Curator Ruthie Dibble with the sundial once owned by the Reverend William Bentley. Photo by Dinah Cardin/PEM.

As Dibble points out, when Bentley became aware of this object around the year 1800, it was already considered ancient and fully recognized as important by this collector and preserver of history and culture.

“I think so many people who continued to give to the Essex Institute and the Peabody Museum in the 19th century were doing so with the spirit of Bentley in mind,” says Dibble.

Curator Ruthie Dibble with the sundial once owned by the Reverend William Bentley. Photo by Dinah Cardin/PEM.

With Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello, American Studies professor and chair of the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at Salem State University, we learn how Bentley was also a hero to Salem Catholics. The popular polymath influenced our 400-year-old city in so many ways, including welcoming European and Canadian immigrant workers who helped shape the city’s culture.

PEM Curator-at-Large George Schwartz, author of Collecting the Globe: The Salem East India Marine Society Museum, weighs in on the history of PEM and how Bentley served as a consultant to its founders. Even before the East India Marine Society (PEM’s founding institution) formed almost 225 years ago, there was the Salem Marine Society. We take you on a private tour of their headquarters to better understand the exclusive nature of these societies and their importance to this port city. Later, Bentley’s diary offers some of the first descriptions of the East India Marine Society's early days, which, as Schwartz says, made up “a period characterized by annual parades and lavish dinners.” Stay tuned for news of a new installation in East India Marine Hall as we approach the 225th anniversary.

Hannah Crowninshield, Portrait of Reverend William Bentley, 1819. Miniature. Museum collection, 1962. Photo by Ani Geragosian and Chris Stepler/PEM.

If you haven’t listened to Part 1 of the episode on Reverend Bentley, go back and put on your headphones for a lovely historic Salem story and soundscape.

Thank you to George Schwartz, Ruthie Dibble and Ben Arlander from PEM, to Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello from Salem State University and to actor Tim Hoover as the voice of Reverend Bentley. This episode was produced by me, Dinah Cardin, and edited and mixed by Erika Sutter. Our theme song is by Forrest James, whose music is on Soundcloud, iTunes and Spotify. The PEMcast is generously supported by the George S. Parker Fund.

Hannah Crowninshield, Portrait of Reverend William Bentley, 1819. Miniature. Museum collection, 1962. Photo by Ani Geragosian and Chris Stepler/PEM.

Music Credits:

Beat Mekanik, “Storia di Archi;” Kirk Osamayo, “(Ambient) Breath;” Podington Bear, “Cascades” and “Theme in G;” Xylo-Ziko, “Flying Fish” and “Pluvio;” Komiku, “The road we use to travel when we were kids;” HoliznaCC0, “Last Train To Earth” and “Quiet Village 1;” Daniel Veesey, Sonata No. 11 in B Flat Major, Op. 22, III. Minuetto; Sergey Cheremisinov, “Slow Light;” Ketsa, “StarTrails;” Alena Smirnova, “Tiny clock;” UNIVERSFIELD, “Cinematic Documentary Ambient;” Nul Tiel Records, “Dark Water;” and Aldous Ichnite, “Dance of the Daedalus.”

PEMcast 35, Part 2: William Bentley as Curious Collector and Consultant

MUSIC

Host Dinah Cardin: It’s 1799. Salem is one of the largest cities in an emerging country. Its ports bustling with ships from around the world. To the Farthest Point of the Rich East would be inscribed on the city’s official seal. Salem’s fleet included the first American vessels to enter many Eastern ports. Mariners left Salem loaded with timber and dried fish. Only to return months later with black pepper, tea and spices. Back home on Derby Street, the atmosphere was filled with excitement and mystery. The shop windows displaying things brought from faraway lands. Elegant women’s clothing, books, table linens. Swarthy sailors grouped together sharing knowledge of distant cultures and the material objects of the places they visited.

Music

Dinah: And keeping track of all of it, was a local Unitarian Minister. The Reverend William Bentley.

Tim Hoover as Rev. Bentley: At Capt. Devereux’s in Salem, I received such things as he had lately brought from Japan. He is the first person who has made a voyage thither from Salem. He exhibited such things as engaged his attention. The Stone Tables, Tea Tables, Servers, Knife Cases, Small Cabinets…(fade)

THEME SONG

Dinah: From the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, welcome to the PEMcast, conversations and stories for the culturally curious. I’m your host, Dinah Cardin. Today, we present the second part of a two-part episode on the life of Reverend William Bentley, the dedicated diarist who left us with pages and pages of his busy life in Salem in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. If you missed Part 1, go back and listen. In Part 2 of this episode, we look at Bentley as an influencer, on what things the Peabody Essex Museum collected more than 200 years ago, on the formation of the East India Marine Society, the very foundation of our museum.

Curator George Schwartz: Well, this summer in August will be the 225th anniversary of the founding of the East India Marine Society.

Dinah: That’s right. Our museum was founded in 1799. It’s the oldest continually operating museum in the US. George Schwartz, PEM’s Curator at Large, has written the history of the Peabody Essex Museum in a book called Collecting the Globe:The Salem East India Marine Society Museum.

George: In the early days of the United States, marine societies had dotted the Eastern Seaboard from Maine to South Carolina. And these organizations provided financial relief for the widows and families of lost or indigent sailors.

Dinah: These societies existed in other port towns and cities north of Boston like Marblehead and Newburyport. There was also the Salem Marine Society, which predated the East India Marine Society. Today, the Salem Marine Society is headquartered in a replica of a ship cabin, atop a popular hotel.

Ben Arlander: We are at the Hawthorne Hotel about to go to the Salem Marine Society.

Dinah: This is Ben Arlander, who works in the IT department at the museum. The Arlander family has deep roots in Salem.

Ben: There is a room of a ship captain on the rooftop of the hotel that doesn’t belong to the hotel. It belongs to the Salem Marine Society, established in 1766. Which may have been the oldest existing non profit organization on American soil. It was established to provide funding for families that lost their husbands or their dad to sea. They would provide funding for navigation purposes. Maybe The lighthouse had to be fixed. They would pay for that. Still today, they would give scholarships for kids to go to Mass Maritime or Maine maritime.

(Sound of getting on elevator)

Ben: (Six please.) If somebody in Salem wanted to do a sailing program, that’s maritime related, so they would pay for that.

Dinah tape to elevator passenger: You are going to learn some history in the elevator.

Italian guy: What are you doing?

Ben: Where are you from?

Guy: I’m from Italy. I’m here to install an exhibition in the Peabody Essex Museum.

Dinah: You never know who you’ll meet in an elevator on the way to a secret room on top of a hotel.

(Sound of going up stairs)

Ben: In the 1920’s, some hotel stakeholders came around and said we would like this location. It overlooks the beautiful green common. And the Salem Marine Society said “Alright, we’ll give you this property at a reasonable price if we can have our own room on the rooftop.”: And that was the was deal.

Dinah tape: Are we going in this tiny door here? No. Good. Oh, Look. Can I take a picture of the sign?

Dinah tape: Cool view.

Ben: This is the mast. The skylight. We have navigation instruments.

Dinah: This room is a replica of the captain's quarters on one of the last Salem vessels to trade in the East Indies.

Dinah Tape: Is there always a bottle of rum? Is that what this is?

Ben: These are the ship logs and anybody who visits the cabin is required to sign in. You want to sign in?

Dinah tape: The ship logs. Can I?

Ben: You want to sign in?

Dinah tape: Yeah. I’m just imagining what the meetings here are like and what you get up to.

Ben: We talk about maritime related things. Things that are going to happen in Salem Harbor, Boston Harbor. All maritime business. This is how we vote. There are white marbles and black cubes. You put a white marble into the slot to say yes. If you want to say no, you put the black cube. It has to be unanimous.

Dinah tape: Love it. This must be so much fun for you.

Ben: I’m a direct descendant of a former ship owner named Elijah Sanderson. He was a furniture maker and cabinet maker and did some work with Samuel McIntire. I traced my descendancy back to him and became a member a couple of years ago. There is an album over here that has photos of every member of the marine society dating back to 1766.

Dinah tape: Wow, these old black and white photos with guys in beards.

Ben: This is Matthew Murray. He was welcomed in because he developed wind charts that helped sailors sail around the world at a faster pace. Until the Civil War, he joined the confederacy and moved to Virginia. To disgrace him they took his picture and turned it around and flipped it upside down and faced the wall. So, he cannot be seen.

Dinah tape: Wow, be stricken from our rolls. Ummm. Who is this on the wall?

Ben: This is Nathaniel Bowditch, a mathematician that took a book from England and revised it called the American Practical Navigator to helps sailors navigate the world just by using the stars. He earned his way into this society as an honorary member. There are three ways you can have membership into this society. Number 1, you can be an honorary member, who is super intelligent or has a career in maritime. You can be a curator of maritime and have access.

Dinah: Just then, as Ben said curator of maritime, we were literally interrupted by PEM’s maritime curator Dan Finamore. Exactly who you expect to run into here, at the headquarters of an exclusive mariner's club.

(Sound of people coming in)

Ben: Yes?

Curator Dan Finamore: Hey.

Dinah tape: Oh, hi.

(greetings)

Dan Finamore: We have some official business.

Dinah: We stepped out onto the roof with Dan Finamore and his guests.

(sound of door )

Dinah tape: Thank you guys. Sorry for all of that. Wow, the museum looks so cool from here.

(Laugher)

Dan Finamore: Hey Ben?

Ben: Yo, what’s up?

Dan Finamore: Hey Ben, do you know where there is a corkscrew?

Dinah: We’ll leave the revelers to have their nightcap on the roof and jump to 1799 when a NEW marine society forms in Salem. The East India Marine Society. The founding organization of the Peabody Essex Museum.

George: Membership was limited to local captains and supercargos who had sailed near or beyond the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn.

Dinah: George again.

George: This founding provision created an exclusive organization that supported the long distance voyages of the town's pioneering mariners.

Dinah: In order to join this exclusive society, you have to have circumnavigated the world to join. That means, leaving Salem’s port in a wind powered ship and not returning for months or years. Like other marine societies, they wanted to aid in navigation and help the families of sailors lost at sea. Sure. But also, part of their mission? To help people see and understand the world.

George: The East India Marine Society also instructed its members, unlike other marine societies, to obtain objects during their voyages to "form a museum of natural and artificial curiosities," which is the founding of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Dinah: And the Reverend William Bentley acted as voyeur, keeping an eye on the formation of a new museum in his city.

George: The albatross, birds of paradise, parakeets, and several birds. No fish, but few insects. (FADE)

FADE TO TIM as Bentley: No fish, but few insects. Some antiquities and a handsome number of coins given by E. H. Derby. A few specimens of stones, ores (not arranged), petrifications and curiosities, in all, one hundred eighty-five articles.

George: What Bentley has described here is what he thought were some things to take note of. You can find entries in his diary where he notes paintings, and his thoughts about how well they were executed, positives and negatives. So, yes, that little bit of critic is very much a through line through a lot of Bentley's entries.

Dinah tape: In your dissertation, you wrote about how Bentley had some of the best descriptions of the new, at the time, museum, in his diary.

George: Well, it's some of the earliest descriptions and a period characterized by annual parades and lavish dinners.

(Fancy music and crowd noise)

George: They would parade with objects that were in the collection to show off.

Dinah: A time of parades and lavish dinners with heavy drinking, smoking and numerous rousing toasts. Parading with museum objects. Can you imagine? Once a year, while carrying a portion of the museum’s collection, these founders would dress up in clothing brought back from their voyages and parade through Salem alongside hired musicians and local military outfits.

George: The first one was on October 14, 1825 to commemorate the opening of this building. A hundred and twenty-three people gathered in East India Marine Hall and they were treated to a sumptuous dinner. Accounts were circulated in newspapers throughout the nation, several which published many of the 51 toasts delivered that night. Imagine how you might feel after raising your arm again and again and again toasting such things as “Success to the Society, whose enterprise and liberality are so strikingly exemplified in this Hall.” Dinah: Bentley, George writes, was put off by their doning of clothing from other cultures, seeing it as racial prejudice and a disservice to their status as members of the elite society.

George: Well, Bentley was very much a critic. You can find things in his diary about how they are trying to build it, things that maybe they can do a little bit more in. And he expressed his disappointment by characterizing the state of the society as "imperfect."

Dinah: Perhaps Bentley was a critic of this new museum in Salem because he himself was a collector.

George: Well, let's step back a little bit to Bentley's arrival in Salem in 1784. He's aged 25.

George: When Bentley arrives, it's 15 years before the East India Marine Society is founded. Bentley was a Renaissance man in many ways. And created an extensive collection of books, flora and fauna, and curiosities. Bentley created a display of his objects within the rooms he rented in the house of Benjamin Crowninshield, today the Crowninshield Bentley House of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Dinah tape:: What would that have been like? Who was seeing it? Who was he showing this to, do you think?

George: I think he would be showing it to personal friends, some of them who were congregants, anyone that he knew that he wanted to bring into his quarters. What he's doing is akin to what was happening in Europe for a few centuries before. These private Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer collections of princes, nobilities, philosophers. What Bentley collects and puts on display in his personal cabinet, some of it is akin to what the East India Marine Society starts to do when they are founded in 1799. He continues to write the objects, the name, the date obtained, and the donor, which the East India Marine Society was doing as well. This occurs over about 22 pages of his diary.

Dinah tape:: He's doing this like he's curating his collection. He's acting like a curator.

George: Yes. I'll give you an example. His diaries reveal active relationships that he had with people that were in his congregation, and many of those were some of the founding members of the East India Marine Society, particularly Captains John Gibaut and Captain Benjamin Hodges.

George: He used this network to procure things that he wanted. Here's an example, on February 26, 1787, he writes in his diary:

Tim as Bentley: Delivered at Captain Gibaut’s, a written request to be forwarded to E. H. Derby that he would purchase one, any, or all volumes of theological works, etc.

George: You could see that he's got specific things that he wants to acquire. It's very much akin to collectors today.

Dinah tape: I think it's funny that point that you made where he literally is ordering. The captains are getting on their boats. They're going off into the world. It's like, instead of going on Amazon to get the package delivered the next day, he's like, "When you guys get back and you come into port, could you have this on the boat for me?"

George: Yes, he doesn't have access. He's not on the ship. He's not going over, but this speaks to Salem, where Salem was at this period where Bentley comes in, and for the next number of decades where, no longer are ships going out of Salem under British rule, they're going across the globe.

Laughing

George: It's not quite Amazon. It's not quite ordering, but he's got access that many others do not to objects in different parts of the world because Salem ships are going to those places.

MUSIC

Curator Ruthie Dibble: To me, he's like the patron saint of curators in America, and that we owe so much to him because before that was a job or a named profession, he was doing that work.

Dinah: This is Ruthie Dibble, PEM’s Robert N. Shapiro Curator of American Decorative Art.

Ruthie: He was living in a town that still very much revered Bentley as both a minister to his flock and also as a collector and preserver of history and culture. I think so many people who continue to give to the Essex Institute and the Peabody Museum in the 19th century were doing so with the spirit of Bentley in mind.

Dinah: We are now inside the museum’s Putnam Gallery, which pairs Native American and American art in On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America. We’re looking at a piece given to the museum that once belonged to Bentley.

Ruthie: We are standing in front of a small, brass object that's about the size of my hand if I spread out my hand. This is considered to be the oldest sundial to have been brought to the Americas by the English. Around 1800 when Bentley becomes aware of this object, it is already ancient and historical.

Dinah: Remember, from Part 1 of this episode, Ruthie tells us that Bentley saw value in what was considered worthless, rejected by most people in Salem. Most families in early America would want to preserve family treasures and not things that belonged to strangers. Not 17th century things from the period of the witch trials, say, or the tools or bowls belonging to someone they don’t know.

Ruthie: Collecting things that were about more than your own family history was a very new idea in early America and reflects both his erudition, because he would have been picking up that idea from his English and European books, but also his originality. Much as curators do now, we often try to be aware of where are important objects that relate to the collection we curate that are out in the wider world. Bentley becomes aware of this sundial in September of 1796. He writes in his diary that he was walking through Governor Endecott's old farm. At the door, he saw the Governor's dial. He remarked that it has the name of the maker on it. Noted all of the script on it. And on the gnomon, the triangle that rises out of the plate, it says the latitude for Salem.

Music

Ruthie: When a sundial is made, in order for it to tell time accurately, it must be made with a particular latitude in mind. So, this one was made in London to represent time at Salem's 42 degrees of latitude.

Dinah: Made to tell time accurately at Salem’s precise latitude, the sundial is both a finely wrought work of art and a highly practical tool, says Ruthie.

Ruthie: This one is particularly precious here in Salem history because it was made for the first governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Endecott. It's an incredible object that's projecting across the Atlantic and into the future how this esteemed governor will live and regiment his time in the colonies.

Dinah: I love that. And if you look on the side, it says Salem right there.

Ruthie: Yes. It says Salem and then it also says the date on it, 1630. It also has the name of the person who made it who was a clockmaker, William Bowyer.

Dinah: Ruthie says that perhaps Bentley loved this sundial because it did something similar to what he was doing with his diary. It marked time.

Music

Ruthie: I think this is a particularly wonderful example that resonates with what we know about Bentley because this is the way that time was known. One of the ways that scholars and even diarists often talk about that work of being a dedicated diarist, is it's a way of keeping time. It's a way of keeping track of your time, keeping track of your days and making sense of that daily regimen. That's really what this object was doing when it came here in 1630, 170 years earlier.

Dinah: Over the years, Bentley keeps revisiting the Endecott farm and his beloved sundial.

Ruthie: He keeps going back, both to enjoy a walk in the countryside and to check on this sundial, which he knows is so important. So, the next time he goes back, he sees that the dial has been broken. The third time he goes back, he says the dial, he says the whole thing's been put in the closet of this rambling old house. It's in the closet because the boys from the farm threw stones and broke off the gnomon. You can imagine him being quietly appalled that this was happening.

Dinah tape: I love that he almost thought he was rescuing it, I think.

Ruthie: Oh, I definitely think he did. I think that he realized that the Endecotts who were living in that farm by that time were so immersed in their family history that they didn't quite see the value of it and that he was going to, in a very kindly and supportive way, make sure that this was in safe keeping.

Dinah tape: It's incredible how shined up it is after, as you say, it sat in someone's yard and all that weather for all those years.

Ruthie: Yeah, there's a little bit of tearing at one edge and damage. Also, we know that the gnomon was broken off, but one of the wonderful things about metalwork, it can be repaired. It's just amazing to think about this, that it sat outside for 170 years and survived as much as it did, as well as it did. Then on April 17th, 1810, he notes in his diary that on this day, he bought the sundial from Captain John Endecott for three dollars, which I did put it in a Google and it comes out as $95 today, which is not that much money. I think it speaks to how little value there was associated with these early New England transatlantic objects that we now treasure so much. After he passed away, the living Endecott's actually took it back from his estate. Then eventually they gave it to the Essex Institute in 1821. By that time, I think it was even more appreciated as an object because of its association with Bentley as well.

Dinah: He could short of shine up an object just by liking it and bringing it into his collection for part of its existence.

Ruthie: Yeah, I definitely think so. He had this knowledge that he shared very openly and just as a collector with a sense of, I'm doing this for a broader community and social purpose. That is really what curators aspire to do today to create collections that benefit the world. I feel indebted to him both because the collection that I curate would not exist if he had not lived, but also because he was one of the first people to take the activities of a curator or an archivist on here in the United States and continues to serve as a model for us today.

MUSIC

Dinah: Despite all of this careful collecting and building of an archive that we enjoy today, Bentley’s role in the formation of the East India Marine Society may have been exaggerated. Some have credited Bentley with being an original founder of the society. The truth, says George, like with most historical questions, probably lies somewhere in between.

George: His role is really sort of a mentor type, because of his influence, but not directly associated with the formation of the society.

Dinah: Captain Nathaniel Silsbee, prominent Salem merchant and later, a US senator, wrote in his autobiography his account of how the East India Marine Society began. And it all started during a huddled conversation in the rain.

George: Which may or may not be true, but he says that quote “The first suggestion of such an institution was made by a few ship masters who were standing together on a cold day under the lee of the store at the end of Union Wharf.”

Dinah: Then, they moved on to a Salem tavern to get things down on paper.

George: They had met at Webb's Tavern in Salem to lay down the structure of this new marine society. In the society's archives, there is a "list of subscribers agreeing to the formation of the organization," which is dated August 31st, 1799. And it notes, "An association of masters or commanders of vessels who have been or are engaged in the East India trade in the town of Salem.”

Dinah: Because Reverend Bentley was a collector whose opinion carried sway across Salem, he was likely working behind the scenes of the fledgling East India Marine Society. Though he was not a founding member. What he did do is function as what we would today call “an influencer.” He was more of a consultant.

George: He couldn't be a member, of course. That's the biggest thing. He could not be a member.

Dinah tape: This is because they were all going out on ships, he was not.

George: Bentley was probably frustrated that the sketch of bylaws that he gave and the further feedback he gave in October were not incorporated into the Eastern India Society's articles. It's a characteristic of Bentley, who had the tendency to be either very supportive or sometimes rather critical of things that would happen in Salem, that you get in his diary entries. Regardless, again, of Bentley's role in the formation of the East India Marine Society, he served as sort of a mentor figure, I’m sure. And his diary served as a valuable source of information on the organization and its collection in the first decades.

MUSIC

Dinah: Just as Bentley influenced the founding of the Peabody Essex Museum, his influence continued into the 20th century. As immigrants found their way to Salem from across Europe via Catholic communities that Bentley had helped foster.

Church bell

Liz Duclos-Orsello: We really can trace all of the churches and all the Catholic communities that exist in Salem and the rich ethnic diversity of the city to the fact that Bentley helped found the first Catholic parish that then became this church here.

Dinah: This is Liz again, the Salem State professor from Part 1 of this episode, who is contributing to a book called Salem Centuries. She’s writing about the history of Catholicism in Salem. A story that traces back to guess who?

Liz: This church, which is now Immaculate Conception, was St. Mary's. But Immaculate Conception as it exists here that we're standing in front of was the birthplace of most of the immigrant Catholic churches that then grew around the city.

Dinah: Among what could have been considered Bentley’s radical views, he helped non Protestants and also actively lobbied for the Freedom of Religion Act of 1811.

Liz: Bentley's really interesting from this standpoint. He was one of the first Unitarian ministers in the United States. Unitarianism had existed since the late 16th century in Europe, but Bentley was an early advocate and devotee and really an evangelist for Unitarianism. What's important about that is that Unitarianism and his particular approach to it was that it was a liberal theology that approached the world with Jesus as a figure whose life of caring for the poor, the sick, those who were outcasts was really the model, as opposed to a Christianity that was about hierarchy. Bentley was someone who didn't have a whole lot of patience for hierarchies. He didn't have a whole lot of patience for pomp and circumstance without having anything to show for it. If you were going to claim some kind of power, that power had to be rooted in doing good. I am fascinated by the fact that he was multilingual. The man spoke and read more than a dozen languages. He consumed information voraciously. Doing that forces you -- not only allows you, but forces you -- to engage in thinking about the world through other people's eyes. I fundamentally see those things as coming together to fuel his interest in constantly questioning the powers that be and thinking about what alternatives to the existing power structure might exist because he had all these different views and these different ways of thinking how the world could be.

Dinah: So years later, when it became clear that Catholics were moving into Salem without a church, who gonna call?

Liz: This initial theological openness and general kindness and welcoming of William Bentley was what spurred the bishop in Boston who knew that there were some folks here in Salem not being ministered to and his was concerned for them and he saw Bentley as an alley.

Dinah: This church, initially led by a priest from County Kerry, served wave after wave of new immigrant Catholic arrivals and launched other ethnic parishes across the city.

Liz: So, if I can make that link between Bentley and early 20th century mill workers who are coming from war and famine ravaged Europe and French speaking Canada, honestly the beginning of that story is William Bentley.

Dinah: Salem’s late 19th and early 20th centuries were shaped significantly by its thousands of Roman Catholic immigrants, says Liz. Drawn to Salem to work in the lather factories, tanneries, and cotton mills, these immigrants built robust communities that transformed this city.

Liz: By the 1870s, 1880s, 1890s, you have a large swath of French-speaking, Quebecois folks coming who begin to worship in what was the Irish Catholic church. They're able to gather and worship together and out of that sprung the establishment of one, then two French Canadian churches with French speaking priests and French speaking masses.

Dinah: Liz points out that these Catholic buildings were never far from key sites of Puritan era Salem and what she calls the city’s Protestant powerbrokers. But this Catholic parish was able to cater to Salemites who shared not only a faith, but language and national origin.

Liz: At the same time, you have the exodus of Polish nationals who are coming to Salem. You have the establishment of a Polish parish, you then have the establishment of an Italian parish. That takes you really from 1820 to 1920, but all of that starts with the establishment of St. Mary's that emerged out of this initial openness. There would not be immigrant catholics in Salem, there would not be catholic communities, without Bentley. Which I think is a surprise for some.

Dinah: Today, mass is offered here at the Immaculate Conception Church in Spanish for the more recent Catholic immigrants. And a plaque commemorates the Unitarian minister who helped start it all.

Liz reads: Immaculate Conception Church, with its beautiful steeple, beckoning to those at sea and on land, continues the mission begun by Salem's early Catholics. The tree of life continues to grow.

Sound of Church bells

George: It’s his diary. Today, it's a resource for scholars and historians to examine, but it's personal reflections. You write a diary not for the audience of many, but for the audience of one, usually, yourself. Many people keep diaries as a means of processing what they're thinking. That either is filled with ebullience and elation for things, or just wonder, but also frustration and dealing with the everyday life and things that occur. This can be read as one of those.

Dinah: Just five years after Bentley criticized the museum, he changes his tune, pointing out that something special is happening here in Salem with this new collection.

George: It shows Bentley’s character. He might be critical, but he also can lavish praise. He is someone who, when he saw something that he thought was being done well, he would point to it.

MUSIC

Tim as Bentley: Spent the morning in the newly arranged Museum of the East India Society in the New Room. They have spared no pains to supply and to decorate it. On one chimney is painted the landing of Plymouth and on another the launching of the Essex with devices. They have the Eastern dresses and arms. Many American curiosities. A good collection of shells and some valuable things in natural history. Upon the whole, their progress has been great and their success equal to any attempt in our country.

MUSIC

Dinah: In 2025, we’ll continue to celebrate the progress of the Peabody Essex Museum.

George: We will open an installation presenting new perspectives on the building they constructed 200 years ago.

Dinah: East India Marine Hall is in many ways the mother ship of PEM. It’s the intellectual, historical and physical heart of the museum. People remember floor to ceiling cases and whale skeletons suspended from the ceiling. Here, our curators will create what George calls a historically evocative environment.

George: The hall is an ideal place to convey the experience and spirit that is uniquely PEM. By exploring our origin story from a fresh perspective, we can gain a nuanced understanding of the continuities of curiosity, inquiry, and inspiration that are at the core of the museum today.

Theme song

Dinah: “Success to the Society, whose enterprise and liberality are so strikingly exemplified in this Hall.” Huzzah!

George: Huzzah!

Laughter

Dinah: There you go.

MUSIC

Dinah: Thanks for listening. Enjoying the PEMcast? Share it with a friend. Or write to us at pemcast@pem.org. Thank you to PEM Curators Ruthie Dibble and George Schwartz and PEM’s Ben Arlander and the Salem Marine Society. Our gratitude to Salem State University Professor Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello and Tim Hoover as the voice of the Reverend Bentley. This episode was produced by me, Dinah Cardin, and edited and mixed by Erika Sutter. Our theme song is by Forrest James, whose music is on Soundcloud, I-tunes and Spotify. The PEMcast is generously supported by the George S. Parker Fund.

Keep exploring

PEMcast

PEMcast 35: The Curious Life of Reverend William Bentley

39 Min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 33: Time Traveling with Curious Objects

1 hr 22 min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 8 | Part 1: Historic House Crush

15 min listen

Audio & Virtual Tours

PEM Walks