This post is from a blog called Conversant, formerly published by the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum.

In July 1783, Benjamin Pickman wrote a letter to his wife, Mary, declaring, “[T]hat Country is my Country whose Laws afford me Protection, where I am free as air, and whose Inhabitants never give me a scornful Look.”[1]

Mrs. Benjamin Pickman (Mary Topan)" John Singleton Copley, ca. 1763, Yale University Art Gallery.

Pickman was writing from England to Mary, who resided with all his family at their home in Salem, Massachusetts. At the writing of the letter, Pickman had been separated from home and family for six years. A second-generation American, a graduate of Harvard and Yale, and a prominent Salem merchant, Pickman was also a Loyalist who chose to ally himself with the British Empire in the conflict with the colonists. At the outbreak of the Revolution, Pickman, like other Loyalists who feared what the consequences of their political choice would be if they stayed in the seat of war, left his American home for England.

Mrs. Benjamin Pickman (Mary Topan)" John Singleton Copley, ca. 1763, Yale University Art Gallery.

With the treaty of peace in 1783, Pickman believed that his exile was finally over and began making plans to return to Massachusetts and rejoin his family. However, the acrimonious news of the reluctance of U.S. states—Massachusetts among them—to accommodate returning Loyalists disillusioned Pickman. When he wrote to Mary in July, he confessed that while he had at first been eager to return to America, now he was not so sure. An America whose citizens met him with a “scornfull Look” and enforced laws that disenfranchised him of his rights and property did not feel like a home. He began making tentative plans to bring his family to England, even declaring that he would move to Japan if it meant that he could be peaceably reunited with his wife. Eventually, Pickman was able to return to the United States in 1785, where he reclaimed what property he could, and resumed his position in Salem society until his death in 1819.

The Atlantic Neptune, volume 1, title page.

I discovered Benjamin Pickman and his family during a research fellowship at the Phillips Library. My primary research related to an atlas called the Atlantic Neptune, in the library’s collection.[2] The Atlantic Neptune was a hydrographic atlas of the North American coast published in London in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. At the time of its publication, it featured the most accurate surveys ever produced of the coastline from Nova Scotia to Florida. Conceived of as an imperial record of British holdings in North America following the Seven Years’ War, the Neptune became a military tool following the outbreak of the War of Independence. This document is part of my larger study of how visual and material representations of the Atlantic Ocean helped people in Britain and America negotiate their identities and global relationships during the period of the Revolution.

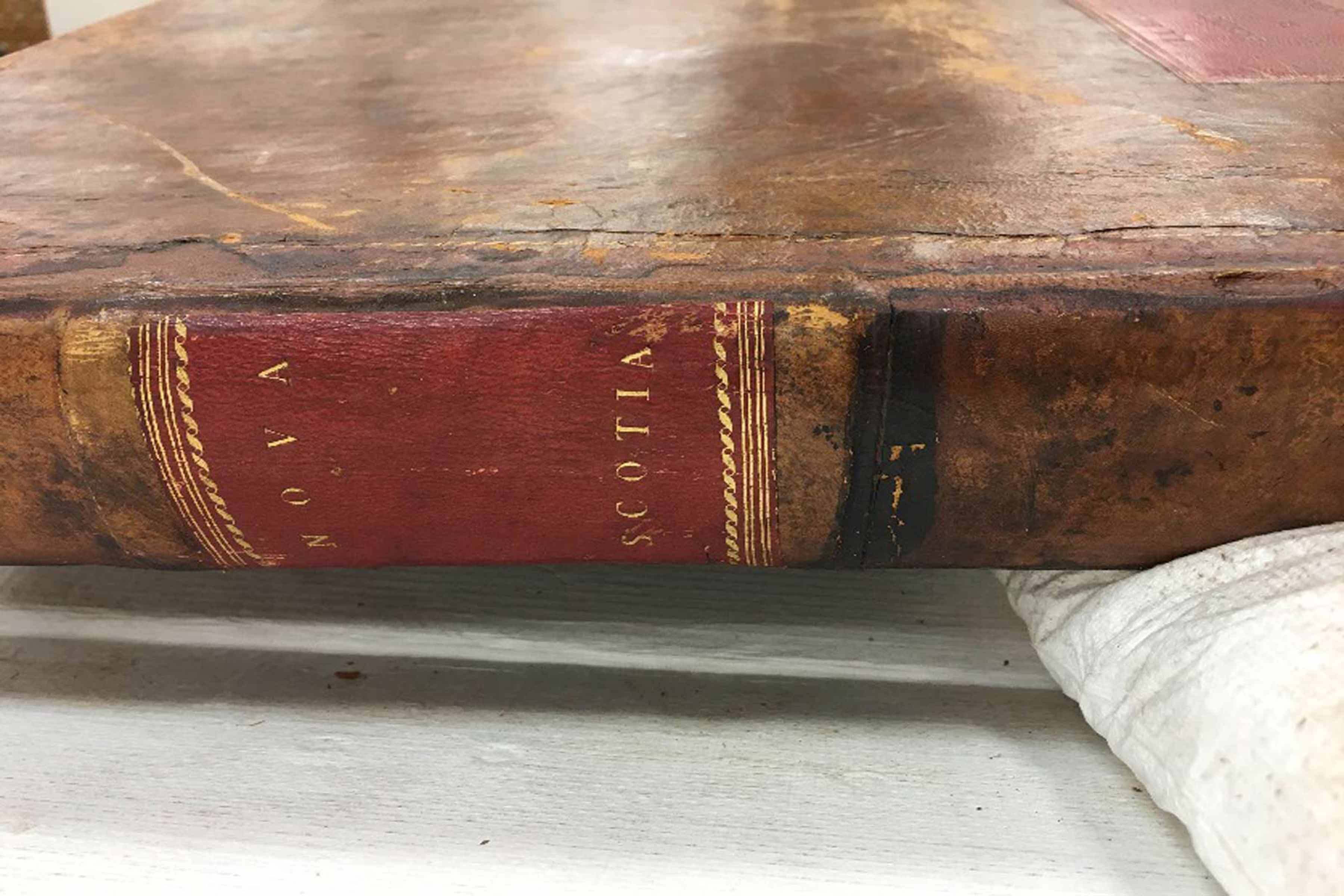

What excited me about the edition of the Neptune at the Phillips Library was that it had a provenance in the collection dating back to the early nineteenth-century. The atlas was donated to the East India Marine Society sometime between its foundation—in 1799—and 1821 by Pickman’s son, Benjamin Pickman, Jr., who was also a Salem merchant.[3]

The Phillips Library also contains the papers of the Pickman family dating from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. [4] The Pickman’s copy of the Neptune consists of the first two volumes of the atlas, which show the coasts and harbors of Nova Scotia and New England—in other words, the family’s home. Thinking about the circumstances under which Pickman would have acquired the British atlas got me thinking about the similarities between his Loyalist experience, and that of the Neptune’s author.

"The Atlantic Neptune," volume 1. Photo courtesy of the author.

J.F.W. Des Barres oversaw the publication of the Atlantic Neptune. A Swiss-born officer of the British Admiralty, he acted as surveyor during the Seven Years War and convinced the Admiralty of the need for better maps of the North American territories. While Des Barres directed the production of the entire atlas, his closest ties were to the maps of Nova Scotia—where he personally led the surveys, and where he also had a home.

Des Barres, like Pickman, was a man with a complex British-American identity. European-born, he was adopted into the British Empire. He had professional ties to the government and metropole, and personal as well as professional links to the colonial province of Nova Scotia.[5] His maps reflect these varying perspectives.

As imperial documents, they frame North American space as under British control—longitude is calculated from London, and place-names reflect British colonization and military victories. However, the precision of the coastal surveys derives from a local understanding of the region, and reflects the weeks and months of habitation required to carry them out. Uniting these local and imperial points of view is the sea itself: by focusing on the coast of North America and picturing the space of the Atlantic Ocean, the maps always infer the global relationship between America and Britain.

The connection between The Atlantic Neptune and the Pickman family got me thinking in a new way about the atlas, but also about the stories we tell of the American Revolution and its aftermath. For Pickman and Des Barres, among other British Americans, continued allegiance to Britain did not contradict their American identities, but rather shaped them.[6] How were their British and Loyalist perspectives of North America incorporated into the culture of the United States? How could the Atlantic Neptune itself shed light on Loyalist experiences? Did the Pickman’s Loyalism or their connections in England create the context for their purchase of the atlas? What kind of meaning did the atlas acquire upon its donation to the East India Marine Society in the nineteenth century? And what does it mean to us to study that atlas in the Phillips Library today?

Emily Casey is a doctoral candidate in the history of art at the University of Delaware. Her dissertation, “Waterscapes: Representing the Sea in the American Imagination, 1760-1815,” explores how eighteenth-century British Americans visualized their place in a global world through representations of the sea in art, literature, and material culture. Emily has received numerous grants and fellowships to support her research from the University of Delaware, the Center for the Advanced Study of the Visual Arts, the Peabody-Essex Museum, and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London in the UK. She is currently the Terra Foundation Predoctoral Fellow for American Art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She is the 2016-2017 Sylvan C. Coleman and Pam Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Emily received her A.B. from Smith College. In addition to her research, she has worked at the Smith College Museum of Art, Winterthur Museum, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Keep exploring

Blog

Graduate students dig into the papers of historic youth activists to tell the story of equal school rights in Salem

7 Min read

Blog

Ongoing effort seeks to identify and correct harmful terms in PEM’s library catalog

5 min read